《삼국사기》 장수왕 본기

一年冬十月 장수왕이 즉위하다 (413)

二年 동진이 왕을 책봉하다 (414)

三年秋八月 이상한 새가 왕궁에 모이다 (415)

三年冬十月 흰 노루를 사냥하다 (415)

三年冬十二月 국내성에 많은 눈이 내리다 (415)

416-419 : 4년 공백

八年夏五月 나라 동쪽에 홍수가 나다 (420)

421-424 : 4년 공백

十三年春二月 신라가 사신을 보내다 (425)

十三年秋九月 풍년이 들어 왕이 잔치를 베풀다 (425)

十四年 북위에 사신을 보내 조공하다 (426)

十五年 평양성으로 천도하다 (427)

428-435 : 8년 공백

二十四年夏六月 북위에 조공하니 북위가 책봉하다 (436)

二十四年 북연 왕 풍홍이 도움을 요청하다 (436)

二十五年 북위가 북연을 토벌할 것임을 알려오다 (437)

二十五年夏四月 북연의 화룡성을 점령하다 (437)

二十五年夏五月 북연 왕 풍홍을 데려오다 (437)

二十六年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (438)

二十七年春三月 북연 왕 풍홍을 죽이다 (439)

二十八年冬十一月 북위에 조공하다 (440)

二十八年冬十二月 북위에 조공하다 (440)

二十九年 신라가 변방의 장수를 죽이다 (441)

442-454 : 13년 공백

四十三年秋七月 신라 북쪽 변경을 침략하다 (455)

四十四年 남송에 조공하다 (456)

457-462 : 6년 공백

五十一年春三月 북위에 조공하다 (463)

五十二年 남송이 왕을 책봉하다 (464)

五十四年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (466)

五十五年春三月 북위가 후궁으로 들일 왕녀를 요구하다 (467)

五十六年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (468)

468 (469 ; 삼국사기)년 경 장수왕이 유연과 지두우를 분할 점령하려 하였다고도 한다. 지두우는 좋은 말의 산지였으므로, 이후 고구려군이 전쟁을 치르는데 큰 도움이 되었다고 한다 (위키)

五十七年春二月 신라의 실직주성을 빼앗다 (469)

五十七年夏四月 북위에 조공하다 (469)

五十八年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (470)

五十八年秋八月 백제가 침입하다 (470)

五十九年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (471)

五十九年秋九月 백성 노구 등이 북위로 달아나다 (471)

六十年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (472)

六十年秋七月 북위에 조공하다 (472)

六十一年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (473) : 백제 개로왕이 북위에 보낸 국서 사건

六十一年秋八月 북위에 조공하다 (473)

六十二年春三月 북위에 조공하다 (474)

六十二年秋七月 북위와 남송에 조공하다 (474)

六十三年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (475)

六十三年秋八月 북위에 조공하다 (475)

六十三年秋九月 백제 한성을 함락하다 (475)

六十四年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (476)

六十四年秋七月 북위에 조공하다 (476)

六十四年秋九月 북위에 조공하다 (476)

六十五年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (477)

六十五年秋九月 북위에 조공하다 (477)

六十六年 남송에 조공하다 (478)

六十七年 백제의 연신이 투항하다 (479)

六十八年春三月 북위에 조공하다 (480)

481 - 491 : 11년 공백 (삼국사기)

489년 : 신라를 공격하여 호명성 등 7개 성을 함락시키고 미질부까지 진격 (위키)

491년 음력 12월, 98세를 일기로 사망하였다. 이 소식을 들은 북위 효문제는 특별히 직접 애도를 표했으며 관작을 추증하고 강왕(康王)이라 시호를 내렸다. (위키)

A. 전쟁으로 본 장수왕과 훈족 고트족의 인물 비교

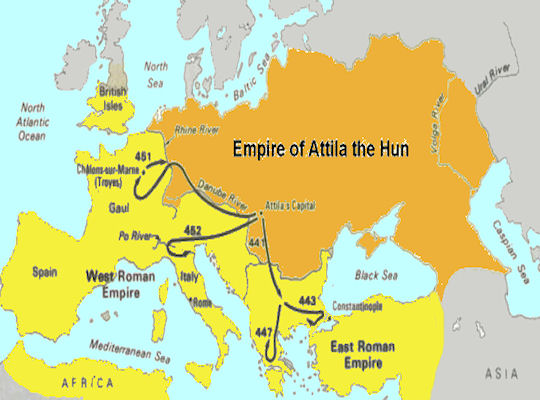

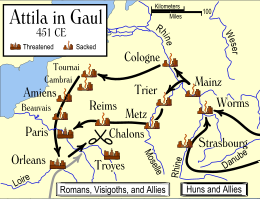

1. 장수왕의 북연 공격(436)과 아틸라의 Gaul 공격 (451)

본 블로그 글, "장수왕의 공격한 풍홍의 북연은 프랑스 북부 Gaul지역에 있었다." 참조

2. 백제 위례성 함락 및 서로마제국의 멸망

- 469 : 백제의 고구려 남쪽 변경 침공

- 472 : 백제 개로왕의 북위에의 국서

- 475 : 위례성 함락, 개로왕 죽음

** 한성백제가 멸망했다는 것에 대한 의문

- 507 : 고구려의 백제 한성(漢城) 공격 실패 -> 즉 한성백제가 475년 무너졌다는 것과 불일치. 한성이 아니라 위례성이 무너졌다는 결론. 일본서기에는 위례성이 무너졌다 기록함.

" 507년 고로(高老)를 시켜서 말갈군과 함께 백제의 한성(漢城)을 공격하려 하였으나, 횡악(橫岳)과 싸우다가 물러났다. " (자료 : 문자명왕, 위키백과)

3. 고구려와 마한에 있는 신라와의 싸움

468 : 고구려의 신라 실직주성, 하슬라 점령

489 : 고구려의 신라 공격 : 호명성 등 7개성 함락, 미칠부까지 진격

4. 479년 유연과 지두우 분할

5. 문자왕 이후 고구려와 신라의 전쟁 : 우산성

497 : 고구려의 신라 우산성 함락

500 : 신라 소지 마립간의 동부 이동 하여 날이군 벽화 만남 및 사망

540 : 성왕시 백제가 우산성 포위, 고구려의 방어

B. 인물사로 본 장수왕(413-491)과 훈족 고트족의 인물 비교

1. Alaric I (391-410)의 태자 Athaulf

광개토태왕의 태자 거련 (巨璉) 임명 : 409년

"Alaric was succeeded in the command of the Gothic army by his brother-in-law, Ataulf,[98] who married Honorius' sister Galla Placidia three years later.[99] Following in the wake of Alaric's leadership, which Kulikowski claims, had given his people "a sense of community that survived his own death...Alaric’s Goths remained together inside the empire, going on to settle in Gaul. There, in the province of Aquitaine, they put down roots and created the first autonomous barbarian kingdom inside the frontiers of the Roman empire."[100] The Goths were able to settle in Aquitaine only after Honorius granted the once Roman province to them, sometime in 418 or 419.[101] Not long after Alaric's exploits in Rome and Athaulf's settlement in Aquitaine, there is a "rapid emergence of Germanic barbarian groups in the West" who begin controlling many western provinces.[102] These barbarian peoples included: Vandals in Spain and Africa, Visigoths in Spain and Aquitaine, Burgundians along the upper Rhine and southern Gaul, and Franks on the lower Rhine and in northern and central Gaul.[102]"

(source : Alaric I, Wikipedia)

2. Attila의 출생년도 및 사망년도의 진실성

- 출생년도 : 395 or 395-403

아틸라는 출생년도에 여러 설이 있지만 어떤 학자는 395년 태생이란 것을 주장한다. 장수왕이 394년 출생으로 우리 역사에서 기록하고 있다. 그리고 장수왕이 죽은 해인 491년에 로마사에서는 이태리를 정복한 그래서 서로마제국을 멸망시킨 오도아케르가 동고트족의 Theodoric the Great에 의해 죽은 해이다.

- 사망년도 : 453, 451년 Gaul 공격후의 죽음 Plot,

고구려 장수왕의 북연 공격 (436) 및 풍홍 구출 및 살해와

송의 사신 왕백구에 의한 고구려 장수 고수의 전사 (438) : 15년 차이

백제 개로왕이 북위에 보낸 국서 (472)에서 고구려 장수왕의 이름, '련(璉)' 언급 : 즉 장수왕의 453년이후 계속 생존 증명

3. 서로마제국 멸망시킨 오도아케르 ( - 491)의 정체성

Sciri 족? 훈족? 고트족?

오도아케르는 중부유럽의 Sciri족 출신이란 주장 (Jordanes 주장)도 있지만 고트족이나 훈족이란 주장도 있다. 로마사는 오도아케르가 서로마제국의 신하이면서 반란을 일으켜 서로마제국을 멸망시켰다 한다.

우리는 여기서 백제의 개로왕이 고구려의 침략에 당하는 역사를 살펴 볼 필요가 있다. 즉 개로왕의 왕권강화 정책에 대하여 귀족들의 반발이 컸는데, 이 와중에서 백제의 장군들인 제중걸루와 고이만년이 고구려에 망명해 고구려 침략의 선봉장이 되어 백제를 공격하고, 개로왕 등을 살해 했다.

로마사의 오도아케르는 제중걸루와 고이만년 중 한 사람이 아닌가 한다. 그러나 오도아케르는 동고트족의 Theodoric the Great 왕에 의해 암살되었다고 한다. 제중걸루와 고이만년 등이 문자왕에 의해 제거된 것이 아닌가 한다. 52년 재위한 Theodoric the Great (475-526)이 문자왕(삼국사기 : 491-519, 서양사 : 475-504)이 아닌가 한다. 장수왕이 북연의 풍홍을 구했던 년도가 삼국사기에 436년으로 나타난다. 그리고 Attila가 Gaul지역을 공격했을 때가 451년으로 나타난다. 즉 15년의 차이가 난다.

4. Alaric II (484 - 507)

78년 재위한 장수왕이 491년 서거했는데, 15년을 더하면 506년이 된다. 서고트족의 Alaric II가 507년까지 재위한 것으로 나타난다. 광개토태왕으로 추정되는 Alaric I은 서고트족 Balt Dynasty 가문에 해당한다. 반면 Theodoric the Great 는 소수림왕으로 추정되는 Ermanaric 가문, 즉 Amal Dynasty가문에 해당한다. 즉 문자왕은 장수왕과 다른 가문의 출신일 수 있다는 것이다. 따라서 Alaric II가 507년 서거한 것으로 기록되는데, 이때까지의 장수왕일 수 있다는 것이다.

즉 장수왕은 Alaric I의 태자 신분인 Ataulf (410-415), 그리고 Attila(435-453), 그리고 Alaric II(484-507)의 모습을 나타난다고 추정된다.

"개로왕은 475년 이전부터 고구려의 침공에 대비했고년 469년에는 고구려의 남부지역을 선제공격하였다. 한편 고구려와 사이에 있는 요충지 청목령(靑木嶺)에 대책(大柵)을 설치, 방어태세를 보강하였다.

472년에는 북위(北魏)에 구원병 파견을 요청하는 국서를 보내, 북위가 백제와 함께 고구려를 협공해야 하는 이유와 성공 가능성을 보고하며 설득하였다. 이는 북위의 세력을 이용해 고구려의 남침세력을 분산, 약화시키려는 개로왕의 외교적인 시도였으나 결국 실패로 끝났다.

당시 남조의 송과 대치하고 있던 북위로서는 요동까지 아우르며 동북아시아의 대 제국으로 발전해 나가는 고구려를 적대시할 수 없는 상황이었다. 개로왕은 전대부터 결성된 제라동맹(濟羅同盟)의 유지·강화에도 힘썼다. 475년에 개로왕이 왕자(뒤의 문주왕)를 보내 구원을 요청하자 신라가 군대 1만 명을 파견해 준 것은 동맹관계에 있었기 때문이다.

개로왕이 이처럼 고구려의 남침 위협에 고심했음에도 고구려의 침공을 받자 백제는 힘없이 무너졌다. 『삼국사기』에 의하면, 백제를 공격한 고구려의 병력은 3만이었는데, 백제는 불과 7일 만에 방어전선이 무너졌고 도성이 공격당해 개로왕은 탈출하는 도중 잡혀 참수되고 말았다.

고구려의 3만 병력에 백제가 이토록 무참히 짓밟힌 중요한 원인 중 하나는 개로왕의 내정의 실패였다. 개로왕은 왕권 강화를 시도해 왕족 중심의 집권체제를 만들었다. 개로왕이 458년에 송나라에 관작제수를 요청한 11명 가운데에는 그의 두 아들 여도(餘都)주 01)와 여곤(餘昆)주 02)을 비롯해 8명이 왕족인 여씨(餘氏)였고, 당시 백제의 주요 세력이었던 해씨(解氏)나 진씨(眞氏)는 없었다.

또한 문주왕은 왕자로서 백제의 최고 관직인 상좌평(上佐平)을 지냈다. 이러한 사실들은 개로왕이 구래의 대 귀족들을 배제시키면서 왕족 중심의 집권체제를 추구했음을 보여주는데, 그것은 왕권강화를 위한 시도이기도 했다....

개로왕은 백제사람으로서 고구려에 망명해 고구려군의 선봉장이 된 재증걸루(再曾桀婁)와 고이만년(古尒萬年)에게 잡혀 살해되었다. 그리고 개로왕이 죽고 문주왕이 즉위하자 구래의 대 귀족인 해구(解仇)의 반란이 있었다.

이는 개로왕의 왕족 중심 정권 운영이 백제 지배층 내에 왕실에 대한 적대세력을 키워냈고, 그로 인해 지배층의 내분이 심화되었음을 보여준다."

(자료 : 개로왕, 한국민족문화대백과, 본블로그, 카테고리, 백제하, 인용글 참조)

"In 476, the barbarian warlord Odoacer founded the Kingdom of Italy as its first king, initiating a new era over Roman lands. According to Jordanes, at the beginning of his reign he "slew Count Bracila at Ravenna that he might inspire a fear of himself among the Romans."[38] He took many military actions to strengthen his control over Italy and its neighboring areas. He achieved a solid diplomatic coup by inducing the Vandal king Gaiseric to cede Sicily to him. Noting that "Odovacar seized power in August of 476, Gaiseric died in January 477, and the sea usually became closed to navigation around the beginning of November", F.M. Clover dates this cession to September or October 476.[39] When Julius Nepos was murdered by two of his retainers in his country house near Salona (May 480), Odoacer assumed the duty of pursuing and executing the assassins, and at the same time established his own rule in Dalmatia.[40]"

(source : Odoacer, Wikipedia)

** 장수왕 (413-491) 자료 - 나무위키

개요

“용성왕 풍씨 임금[1]이 야숙을 하고 있으니 병사와 말이 피곤하겠소.”"龍城王 馮君 爰適野次, 士馬勞乎."

- 북연 황제 풍홍이 고구려로 도망쳐 왔을 때 비꼬며 건넨 위로의 말. 삼국사기 발췌.

'장수왕은 이름이 거련(巨連)이고(일설엔 연(璉)이라고도 한다), 개토왕의 원자(元子)이다. 체격과 외모가 걸출했으며 그 의지가 크고 위대했다...'

- 삼국사기 고구려 장수왕 본기에 나오는 첫 문구.

고구려 왕조 제 20대 군주. 394년에 광개토대왕의 아들로 태어나 413년 음력 10월, 19살 때 왕위에 오르고 491년 음력 12월, 97세를 일기로 승하하며 재위를 마쳤다.

2. 시호와 휘

《삼국사기》 고구려 본기가 전하는 시호는 '장수왕(長壽王)'이다. 실제로 오래 살았다는 뜻의 장수다.[2] 이 의미의 將帥王이 아니다. 오래 살아서 장수라는 시호를 올렸다는 해석이 대세이고 종종 불교 용어 장수와 연관짓기도 한다.[3] 당시 고구려가 불교 진흥 정책을 밀고 있었다는 점을 생각해보면 자연스러운 주장이다.

휘는 거련(巨連). 단순 한자 풀이론 '크게 잇는다'는 뜻. 아마도 부왕인 광개토대왕의 뜻을 잇는다는 의미일 듯 하다. 중국에선 줄여서 연(璉)이라 기록했다.

북위에서는 강(康)이라는 시호를 주기도 했다.

3. 압도적인 재위기간 장수왕 재위기간의 위엄

시호인 장수(長壽)의 의미처럼 매우 오래 산 임금이다. 고대인 기준으로도 그리 오래 살지 못한[4] 아버지 광개토대왕과 무척 대비되는 부분. 의학이 매우 발달한 21세기에도 96세까지 생존하기는 무척 어려우며, 5세기 당시의 의학과 평균 수명을 고려하면 정말 오래 장수했다고 밖에 볼 수 없다. 158세까지 살았다고 전해지는 수로왕, 119세까지 살았다고 전해지는 태조왕 다음으로 한국 역사상 가장 오래 산 군주로 전해져 오는데, 역사적 모순점이 많고 신화적 기록이 가미됐을 것으로 여겨지는 수로왕이나 태조왕과는 다르게 장수왕은 교차검증 가능한 실증적 재위 기록이 존재하기에 일말의 의혹 없이 확실한 역사적 팩트로 받아들여지고 있다. 다시 말해, 실질적으로는 한국사에서 가장 장수한 왕이라고 볼 수 있다.

게다가 재위 기간은 무려 79년. 83세까지 52년간 조선을 다스리며 조선 역사상 가장 오래 재위한 영조나 고려 역사상 최장기 집권 군주이자 최장수 군주인 고종(45년), 발해 역사상 최장기간 재위 군주인 문왕(57년)보다도 재위 기간이 길고 더 오래 살았다.

위의 연도를 보다시피 5세기 초부터 5세기 말까지가 장수왕의 치세라 사실상 5세기의 고구려는 장수왕의 단독 치세였다고 봐도 무방할 정도로 엄청 길다(…). 원래 후계자였던 태자 조다는 부왕이 너무 오래 재위한 탓인지 아버지보다 먼저 세상을 떴고, 후대의 영조[5]나 프랑스 부르봉 왕조의 루이 14세[6]처럼 손자인 문자명왕이 장수왕에게 보위를 이어받아야 했다.

같은 고구려의 왕들인 태조왕, 신대왕, 차대왕[7]등이 믿을 수 없는 장수로 이름이 높고 미천왕, 고국원왕, 문자명왕등도 3~40년에 달하는 재위기간을 자랑하며 안장왕, 영양왕, 영류왕등도 환갑쯤은 가뿐히 넘기는 레벨의 장수를 자랑 하는 것을 보면 고구려 왕가 자체가 장수하는 집안이었을 가능성이 높다. 장수는 유전자에 영향을 굉장히 많이 받기때문.

알다시피 왕의 수명은 국가의 존망을 좌지우지하는 요소이고 왕은 살아있다는 사실 그 자체로 국가의 상징이기 때문의 왕의 생존은 그 자체로 의의를 갖는다. 96세까지 고구려를 통치하며 패권국으로 각성시킨 장수왕은 당시의 백성와 신하들에게 말 그대로 살아있는 신으로써 비춰졌을 것이다.

4. 치세

보통 아버지인 광개토대왕의 활발한 정복 사업을 접고 뒷수습과 남진정책으로 선회한 수성군주의 이미지가 강하다. 광개토대왕만큼 적극적이지는 않고 내치에 주력한 시기도 있었지만, 실상은 한국사 전체를 통틀어 아버지 이외에는 비견할 대상을 찾기 힘든 패왕 타입의 정복군주다.

북쪽으로는 몽골 초원으로 말을 달려 지두우 분할을 시도하는 동시에 거란과 물길을 압박하고, 서쪽으로는 요서 일대에서 북연의 절대 투항을 이끌어내 황제를 포함한 황족과 인구를 접수하고 외교전략을 병행하여 북위를 상대로 기싸움에서 유리함을 선점했으며 남쪽으로는 한강 유역과 충청도는 물론이고 경상도 일대와 일본 열도에까지 매우 적극적인 군사 활동을 벌였다.

아버지 광개토대왕이 미처 못 이룬, 고구려의 두 원수 후연[8]과 백제의 수도인 화룡성과 위례성을 불태우고, 북연 황제 풍홍과 백제 임금 개로왕을 죽여 아버지의 못 이룬 한을 풀었다. 거기에 신라의 실성 마립간의 죽음과 눌지 마립간의 즉위에도 고구려가 관여했다는 기록도 있고 백제의 비유왕이 고구려에게 암살되었다는 설도 있다. 최소 2명, 최대 4번이나 다른 나라 임금을 갈아치운 무시무시한 사람이다. 저 시기에 백제는 신라의 지원이 없었다면 고구려에게 짓밟혀 나라 자체가 멸망할 뻔 했다.[9] 여하튼 중국 황제를 죽이고 황성을 불사른 한반도의 군주는 장수왕이 유일하다.

이 때 고구려는 내적으로나 외적으로나 잘 나갔겠지만 아버지가 넓힌 땅, 흡수한 북연의 인구, 평양성 천도로 인해 생겼을지 모르는 신, 구세력의 대립, 물길의 발흥, 북위의 압박, 고구려의 세력에서 이탈하려고 나제동맹을 맺어 안간힘을 쓰는 백제와 신라의 도전 등 나름 골머리 앓으면서 신경을 쓸 일이 많았을 것이다. 그 상황에서 장수왕은 이러한 과제를 훌륭하게 수행해 고구려는 본격적으로 과거와 급을 달리하는 동아시아 강국으로 자리잡는다.

4.1. 내치

《삼국사기》에 기록된 내정 관련 기록이 워낙 빈약하여 주변국에서 장수왕 대 고구려를 기록한 글(개로왕의 상표문 등)을 바탕으로 당시 고구려는 장수왕이 왕권 강화를 위해 귀족들을 압박하여 전성기를 이루었다고 추측한다.

414년, 만주 일대에 광개토대왕릉비를 건립했다. 아버지인 광개토대왕의 업적을 기려서 고구려 왕실의 권위를 세우고, 주변국과의 관계를 규정하며, 광개토대왕 때 입안된 수묘인 제도를 성문화하기 위한 조치라고 볼 수 있다. 다만 이건 손자인 문자명왕 때 건립됐다는 설도 있다. 광개토대왕릉비의 건립 시점을 장수왕 시기로 보느냐, 문자명왕 시기로 보느냐는 건립 목적과 관련되어서 중요한 부분이라 논란이 많다.

경주시 호우총 그 유명한 호우명 그릇도 장수왕 3년(415년)에 제작 되었다. 바닥에 씌여진 문구는 "을묘년국강상광개토지호태왕호우십(乙卯年國岡上廣開土地好太王壺杅十)"으로 "국강(國岡) 위에 있는 광개토대왕릉용 호우"라는 뜻이다. 한마디로 광개토대왕의 제사를 위해 만들어진 제기인데, 어째서 신라로 흘러들어왔는지는 불명.

419년 여름, 나라의 동쪽에 홍수가 나서 사신을 보내 위문했다.

424년, 나라에 풍년이 들어 왕이 군신들에게 잔치를 베풀었다.

4.1.1. 평양성 천도

평양성 천도와 관련해서는 이미 아버지인 광개토대왕대 부터 평양으로의 천도를 염두해 두고 있었고[10], 장수왕은 부왕의 정책을 이어받아 평양성 천도를 단행했다.

기존 고구려의 수도였던 국내성은 동천왕 때의 경험으로 그다지 방어하기 좋지 않은 곳이라는게 입증된 데다 척박하기까지 하여 생산력이 후달리는 곳이였다. 이 곳의 겨울 평균 기온 -11℃. 쉽게 말하자면 철원보다 겨울에 6도 정도 낮은데, '냉대 동계 건조 기후(Dw) + (한반도보다) 내륙 지방 + (평양성보다) 고위도'라는 악조건 덕분에 여름엔 철원보다 더운데다 춘천 평야의 반에 불과한 좁은 평야 외 모두 산이다.

반면 평양성 지방은 황해도의 평야와 인구 밀도를 바탕으로 높은 생산력을 가지고 있음은 물론 고조선의 후기 수도였다는 점과 낙랑군에서도 행정 중심지였던탓에 당대 동방(중국 동방)의 정치, 문화, 경제 중심지였다. 더구나 백제, 신라, 가야의 세력을 미리 꺾어두었기 때문에 이들로부터 불의의 습격을 당할 위험도 적은데다[11] 떠오르는 강자 북위를 방어할 만한 위치였다. 이때 건설된 궁궐이 바로 안학궁(安鶴宮)이다.

4.1.2. 내부 분쟁의 가능성?

개로왕이 472년에 북위에 보낸 국서에 "지금 연(璉)[12]의 죄로 나라는 어육(魚肉)이 되었고, 대신들과 호족(豪族)들의 살육(殺戮)됨이 끝이 없어 죄악이 가득히 쌓였으며, 백성들은 이리저리 흩어지고 있습니다."라는 문구가 등장한다.[13]

4.1.3. 국호 변경

평앙 천도를 기점으로 고구려의 국호는 고려(高麗)로 굳어지기 시작했다. 광개토대왕대의 중원 고구려비에서 고려태왕(高麗太王)이라는 명문이 등장하므로 고려라는 국호는 이미 전대부터 존재했으나 국호가 고려로 굳혀진 시기는 장수왕대로 본다. 중국의 기록에서도 장수왕 재위시기 부터 고구려를 고려라고 일관적으로 기록하기 시작한다.

다만 최소 고려시대부터는 고구려라는 국호가 더욱 보편화되어 있었다.《삼국사기》가 좋은 예이다. 현대의 학계에서도 왕건이 건국한 고려 왕조와의 혼란을 피하기 위해 여전히 고구려라 부르고 있다. 조경철 등을 비롯한 다소 급진적인 소수의 연구자들은 아예 고대의 고구려와 중세의 고려를 각기 전고려 · 후고려라 불러야 한다고 주장하지만 이미 오랜 세월 동안 한국인들이 고구려와 고려로 구분해온 마당인지라 별다른 반응은 없었다.

4.2. 외정

내정이나 외정이나 고구려 자체의 사료가 거의 없다. 외정 관련 기록은 주변국에서 남긴 것들이 퍽 있기 때문에 그나마 사정이 나은 편. 특히 중국에서는 조공, 책봉 기록의 양이 후덜덜하고 중국과의 교섭 과정에서 벌어진 사소한 사건들도 주목할만하다. 일본에서는 신라가 고구려로부터 이탈하는 과정을 꽤 자세하게 기록으로 남겼다. 물론 장수왕 대로 추정되는 시기의 일본과 고구려의 교섭도 기록으로 남아있긴 한데 《일본서기》의 이주갑인상 때문에 정확하게 장수왕 시기의 기록인지는 확실하지가 않다.

4.2.1. 남진 정책

신라에서 사냥을 하던 고구려 장수가 살해당하는 사건이 발생했다. 이후 신라에 주둔했던 고구려 장수가 자신의 신라인 부하에게 우리나라가 너희 나라를 멸망시킬 것이라고 불어서 경각심이 생긴 신라 측에서 신라 내의 고구려 군인들을 몰살해버렸다. 이렇게 신라가 고구려의 영향력에서 완전히 벗어나게 되었다. 그러나 신라는 갓 고구려의 영향력에서 벗어난 터라 아직 단독으로 고구려에 단독으로 비빌 국력은 안되었기에 백제와 힘을 합쳐 나제동맹을 체결하고 장수왕의 남진에 대항했다. 이 때는 둘을 합쳐도 고구려보다 강하진 않았지만, 그래도 대륙의 북위, 유연 등과 국경을 접한 고구려는 백제 - 신라 - 가야가 소백산맥을 끼고 하는 방어선을 완전히 제압할 정도의 전력 투사가 사실상 무리였다.

장수왕 대에 신라와 고구려의 국경 지대에서 잦은 마찰이 발생했는데, 450년엔 신라의 하슬라 성주 삼직(三直)이 고구려 변경 성주를 살해하는 사건이 벌어지기도 했다. 468년 장수왕은 신라를 공격하여 하슬라와 실직성를 점령했다.

한편 백제의 개로왕이 북위에게 밀서를 보내 고구려를 침략을 해달라고 요청한 사실이 472년 고구려 국내에 전해졌다. 장수왕은 첩자인 승려 도림을 백제에 파견하여 개로왕이 왕권을 강화한다는 목적으로 궁궐 등을 짓게 하여 국고를 낭비하게 했다. 백제의 국고가 바닥날 낌새를 보이자 475년 장수왕은 백제를 전격적으로 침공해 수도 위례성을 함략하여 개로왕을 비롯해 여러 왕족과 귀족들을 죽여 고국원왕의 원수를 갚았다(475년). 이때 비로소 우리가 교과서에서 흔히 보는 고구려의 남방 강역의 확장이 이루어졌다. 이 때 직접 출병한 장수왕은 나이는 82세.

위례성 함략 때 살아남은 백제의 왕자 문주[14]가 신라 지원군을 이끌고 웅진성에 들어가 항전 태세를 갖추자 장수왕은 파죽지세로 남진하여 웅진....까지 내려와 산성을 쌓았다(월평산성). 자세한 기록은 없지만 웅진성과 대전 사이에서 장수왕의 고구려군과 나제 연합군의 치열한 교전이 있었던 것으로 추정되며, 결국 장수왕의 고구려군을 저지하는데 성공한 백제는 멸망 위기에서 가까스로 살아남게 된다.[15]

백제를 딴 뒤 숨을 고른 장수왕은 481년 이번에는 신라를 침공하여 신라 북변 7개 성을 점령하고 계속 진격하던 중 신라, 백제, 가야 연합군에게 격퇴당했다고 하고 고구려군이 무려 모산성에까지 출몰하였다고 한다.

남한지역에서 남진 정책과 관련된 고구려 유적들은 발굴조사의 누적이 상당히 진행되었고 이러한 인식을 바탕으로 양주분지에 위치하는 여러 보루들까지도 2018년인 현재 조사되고 있다.

보루를 통한 고구려의 진출방식은 한탄강, 임진강을 기점으로 이뤄지는 것으로 추정되고 있다. 황해도에서의 주도권을 장악한 고구려는 임진강, 한탄강에서 백제와의 국경을 형성하였고 이를 넘어 양주분지 일대를 장악하였고, 나아가 아차산 일대 보루군을 설치하면서 한강 유역에 대한 공세를 펼쳐나가 475년 한성을 공략하는 것으로 추정된다. 고구려 보루들은 서술한 3개의 권역에 주로 분포하고 있다.

한강 이남의 대전 월평동 유적(목책), 안성 도기동 목책, 청원 남성골 산성(목책)에서는 공통적으로 고구려 토기들이 확인되고 있는 점으로 백제에 의해서 형성된 방어시설을 고구려가 지속 남하하여 점령 후 사용하였음을 알 수 있다. 또한 가장 남쪽인 대전 월평동 유적에서 고구려 토기가 나오고 있는 상황은 웅진의 상황이 얼마나 다급했는지 알 수 있는 대목이다. 웅진의 바로 옆인 현재의 세종시 나성동 유적에서는 고구려 토기가 확인된 사례도 있다.

이후 경기 이남지역이 다소 혼란해지는 상황에서 신라의 한강 진출이 시도되면서 고구려와 마찰을 빚게 된다. 이때 고구려는 위의 보루들을 보강하여 신라와의 전쟁에서 활용하기도 하였다.

기사는 간단하게 나오지만 삼국사기나 조선왕조실록의 지리지를 보면 경상북도 거의 절반 정도에 고구려의 행정구역이 기록되어 있다. 또한 고구려군이 무려 모산성에 등장하고 왜국도 고구려의 공격을 받아 출항이 힘들 정도였으니... 각각 백제, 신라, 대가야의 왕성 반나절 거리까지 고구려의 국경이 밀고 들어왔으니 한반도 남부의 상황이 얼마나 절박했을지 짐작이 간다. 4.2.1.1. 관련 문서

4.2.2. 왜와 교섭

한편 《일본서기》에 의하면 고구려가 백제 한성을 함락시켰을때 고구려 장수들이 더 치고 내려가 백제를 완벽하게 멸하자고 건의하자 장수왕이 백제의 뒤에 야마토가 버티고 있다는 식의 핑계를 대면서 거부하는 장면이 나온다. 실제 기록에는 장수왕이 뜬끔없이 백제가 야마토(왜)의 속국이라는 것은 다 알고있는 상식이라고 말한다.[16] 그냥 수사 다 띄고 백제 - 신라에 야마토까지 본격적으로 합세한 반고구려 동맹을 우려한 것으로 보면 된다.

참고하기위해 그 내용을 아래에 적어놓는다. 20년 겨울에 고구려 왕이 크게 군사를 일으켜 백제를 쳐서 없앴다. 그런데 몇몇의 남은 무리들이 창고 아래에 모여 있었다. 무기와 양식이 이미 다떨어지고 근심하여 우는 소리가 매우 심하였다. 이때 고구려의 여러 장수들이 왕에게 “백제의 마음가짐이 범상치 않습니다. 신들이 볼 때마다 자신도 모르는 사이에 제 정신을 잃습니다. 다시 덩굴이 뻗어 자라듯 되살아날까 두렵습니다. 뒤쫓아 가서 제거하기를 청합니다.”라고 말하였다. 이에 왕이 “그럴 수 없다. 과인이 듣기에 백제국은 일본국의 관가(官家)가 된 것이 그 유래가 오래되었다. 또한 그 왕이 들어가서 천황을 섬긴 것은 사방에서 모두 아는 바이다.”라고 말하니, 그만두었다.

【『백제기(百濟記)』에서는 개로왕(蓋鹵王) 을묘년 겨울, 고구려(狛)의 대군이 와서 대성(大城)을 7일 낮 7일 밤을 공격하였다. 그리하여 왕성이 함락되고 마침내 위례(尉禮)를 잃었다. 국왕과 대후(大后), 왕자 등이 모두 적의 손에 죽었다고 적고 있다.】.

《일본서기》 웅략기 20년. 고구려가 백제를 쳐서 없앰

《일본서기》에 의하면 고구려에서 온 사신이 왜왕 앞에서 외교 문서를 읽는데 그 내용이 고구려 왕이 교한다(=가르친다)라는 것이라서 왜의 왕자가 그 문서를 찢어버렸다고 한다. 왜왕이 남조에 보낸 외교 문서에 의하면 고구려가 왜의 변경을 약탈하고 사신을 차단해서 제대로 사신을 보낼수 없다고 하소연하는 내용이 나온다.

4.2.3. 남북조시대의 고구려

중국인 입장에서 쓴 중국 사서에는 조공을 했다고 말하나 일본 서기와 같이 외국 사신에 대한 기사는 무조건 조공으로 기록한 중국 사서를 그대로 사실로 믿는 것은 안된다는 비판도 있다.[18]

북위의 위협에도 효과적으로 대처했다. 후연(後燕)이 멸망한 직후 건국 된 북연(北燕, 407년 ~ 436년) 2대 황제 풍홍은 북위가 북연을 멸망시키려 하자 고구려에 구원을 요청했을 때(436년), 장수왕은 갈로와 맹광의 지휘 하에 군사 2만을 파견해 화룡성의 주민들을 구출한뒤 화룡성을 약탈, 방화하고 돌아왔다. 북연 황제 풍홍은 고구려로 망명했다가 분수를 모르고 대접을 바라다가 더 천대를 받게 되었다.[19] 이후 풍홍은 송(육조)(宋, 420년 ~ 479년)에 망명을 요청하게 되고, 결국 풍홍은 이 때문에 장수왕에게 죽임을 당했다. 이후 남북조 사이에 등거리 외교가 본격적으로 시작되는데 송 태조가 북위를 공격하고자 말 800필을 송나라에 지원하여 송나라와 해빙하고 북위를 압박하기도 한다.

물론 고구려의 위세가 남북조를 압도할 정도는 아닌지라, 송의 사신이 이 때 풍홍의 잔당군으로 풍홍을 죽인 장수를 죽이고도 송의 형식적인 처벌만 받은 사건[20][21] 이 있기도 했다. 하지만 역대 중국 왕조들이 이렇게 형식적으로나마 처벌한 경우도 거의 없었던 것으로 보면 그당시 고구려의 국력이 상당히 강력했다는 반증은 된다.[22]

이후 북위는 고구려 왕실과의 혼인을 바랐지만 장수왕의 한 신하가 "저 놈들 연나라도 저렇게 뺑끼치고 침공했음"이라고 하는 바람에 없던 일이 되었다. 그러나 10여년 뒤에는 역으로 고구려 측에서 북위에게 요구하여 혼인이 성사된다. 이때 고구려에서 북위로 건너간 자가 문소황후로, 그녀의 오빠 고조는 북위의 권력자가 되어 북위의 정계를 주무른다. 그래서인지 삼국사기에 장수왕이 승하했을 때 북위 황제가 애도 의식까지 치렀다고 한다.

참고로 일부에서는 장수왕이 북위에 역대 황제의 계보를 바치도록 요구하였고 이에 응한 북위가 황실 계보를 바쳤다는 식으로 알려져 있지만 이는 해석의 오류로 기실 북위가 신하국으로서 계보를 고구려에 바친 것이 아닌 고구려가 봉물을 바치면서 일종의 조공국으로서 북위 황실에 대한 피휘(避諱)를 하기 위한 이유로 원한 것이다.

여하간 이 당시 고구려는 북위, 송보다 강성한 것은 아니었지만 서로가 함부로 건드릴 수 없는 수준의 비교적 강한 국력을 자랑했다. 이 때 고구려는 북위, 남조, 유연과 함께 동아시아 4강 체제를 구축하는데 성공한다. 중국의 국가들은 경쟁적으로 고구려에 최대한의 높은 직위를 내리면서 고구려를 자신들 편으로 끌어들이려고 꾸준히 노력했다. 중국 국가들이 내린 작위 기준으로 장수왕보다 높은 위치에 오른 국왕도 찾아보기 어려울 정도. 기껏해야 원 간섭기 몇몇 고려 왕들 정도가 고작인데[23] 독립국이었던 고구려와는 그 위상을 논할 순 없다. 고구려가 북위를 공격하고, 북위 사신의 고구려 통과를 불허하고, 대놓고 양다리 외교를 펼치는 등 피책봉국답지 않은 태도를 보여도 북위는 고구려를 함부로 대하지 못했을 지경. 토욕혼, 유연, 남조는 틈만나면 괴롭히면서도 고구려는 한 번도 건드린 적이 없었다.

남제서(南齊書)에 따르면 북위에서 사신을 대우할 때 남제의 사신과 고구려의 사신을 동등하게 대우해 남제의 사신들이 불평했다는 기록이 남아있다. 489년(장수왕 77년)에 효문제가 고구려 사신을 제나라 사신과 동급으로 대하자 제나라 사신이 항의한 사례가 대표적.

또한 삼국사기에도 북위가 사신들의 숙소를 배치할 때 남제의 사신을 첫번째로, 고구려의 사신을 두번째로 두었다는 기록이 있다.

4.3. 지두우 분할 시도

이후 479년에 몽골 고원의 유연과 모의하여 현재의 대흥안령(大興安嶺)에 위치한 유목민 부족 국가인 지두우의 분할을 시도했다. 유연과 지두우 분할 모의를 했다는 기사만 남아있고 그 경과에 대해서는 기사가 남아있지 않기 때문에 성공 여부는 알 수 없다. 다만 지두우와 고구려 사이에 있던 거란이 고려(물론 고구려)의 침략을 받아 대릉하 인근으로 도망했다는 기록이 2건이나 확인되는 것으로 보아 성공 여부는 차치하고서라도 분할 시도는 했던 것 같다. 헌데 그때 유연은 북위에게 털리고 있던 터라 지두우를 원정한 사정이 못되었고 이후에도 지두우나 물길이 여전히 사신들을 보내 외교활동을 하는걸로 보아서는 실패했거나 완전히 삼키지는 못했을 가능성도 무시할수 없다. 확실한 건 지두우 원정 성공 여부를 떠나서 시도는 이루어졌고 그 와중에 거란이 고구려에게 침략당하여 당시 내몽골의 유목민 세계에 혼란을 야기했다는 것. 종종 내몽골에서 발견되는 고구려 계통의 성터를 이 사건과 연관짓기도 한다.

국사 교과서에는 역사 부도 표기에는 거의 나타내지 않되 흥안령 일대의 초원 지대를 장악하였다는 서술을 남김으로써 두리뭉실하게 다루고 있다.

5. 평가

한 나라의 운명을 결정짓는 중요한 시기가 3대라고 이야기한다. 고구려의 경우가 저 3대에 빗댄다면 소수림왕-고국양왕 시대가 1대로 무너진 나라를 재건하여 힘을 다시 비축했고 2대가 광개토대왕으로써 비축한 힘으로 주변국을 정복하고 다녔다면 3대인 장수왕은 넓어진 나라를 다스릴 체제를 다시 재구축하고 전대에 과제들을 해결하야했다.

넓어진 영토, 점점 다시 강해지는 남북조와 고구려의 빈틈을 시시각각 찾고있는 백제와 신라를 사방에 두고 장수왕은 훌륭하게 문제를 해결한 명군으로 평가받는다. 평양으로 수도를 이전하며 국내성 주변에 힘을 길러온 귀족들을 타파하고 왕권을 강화시켰으며 고구려의 체제를 정비했다. 동시에 남쪽으로 수도를 옮김으로서 남벌을 천명하며 실제로 백제와 신라를 제압했다. 신라가 광개토대왕 시기만큼에 장악력을 두려워하여 세력권 밖으로 나가기는 하였으나 백제와 신라는 최소한 장수왕 당대에는 고구려에 힘에 짓눌려 있었다라고 표현해도 무리가 없었다. 남북조에게는 양면외교를 시행하며 형식상 조공을 주었으나 실질적으로는 대등한 외교로 동북아를 남북조, 유연과 함께 4강체제로 평화를 정착시켰다.

결론적으로 장수왕은 광개토대왕 다음 대의 왕으로써 편하게 국가를 운영했을것처럼 보이지만 의외로 여러 문제들을 해결해야할 시대적 상황에서 집권했다. 하지만 탁월한 본인의 능력을 활용하여 강해진 고구려의 국력을 바탕으로 안으로는 왕권 강화, 밖으로는 주변국 장악을 성공적으로 이루었으며 본인도 장수하며 강력한 고구려의 국력을 향유한 왕이다. 실제로 장수왕이 받은 중국 남북조의 왕호들과 지위들 주변국의 대접들은 역대 한반도의 군주들 중에 당연히 최상위라고 할만했다

6. 삼국사기 기록

《삼국사기》 장수왕 본기

一年冬十月 장수왕이 즉위하다 (413)

二年 동진이 왕을 책봉하다 (414)

三年秋八月 이상한 새가 왕궁에 모이다 (415)

三年冬十月 흰 노루를 사냥하다 (415)

三年冬十二月 국내성에 많은 눈이 내리다 (415)

416-419 : 공백 (4년)

八年夏五月 나라 동쪽에 홍수가 나다 (420)

421-424 : 공백 (4년)

十三年春二月 신라가 사신을 보내다 (425)

十三年秋九月 풍년이 들어 왕이 잔치를 베풀다 (425)

十四年 북위에 사신을 보내 조공하다 (426)

十五年 평양성으로 천도하다 (427)

428-435 : 공백 (8년)

二十四年夏六月 북위에 조공하니 북위가 책봉하다 (436)

二十四年 북연 왕 풍홍이 도움을 요청하다 (436)

二十五年 북위가 북연을 토벌할 것임을 알려오다 (437)

二十五年夏四月 북연의 화룡성을 점령하다 (437)

二十五年夏五月 북연 왕 풍홍을 데려오다 (437)

二十六年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (438)

二十七年春三月 북연 왕 풍홍을 죽이다 (439)

二十八年冬十一月 북위에 조공하다 (440)

二十八年冬十二月 북위에 조공하다 (440)

二十九年 신라가 변방의 장수를 죽이다 (441)

442 -454 : 공백 (13년)

四十三年秋七月 신라 북쪽 변경을 침략하다 (455)

四十四年 남송에 조공하다 (456)

457-462 : 공백 (6년)

五十一年春三月 북위에 조공하다 (463)

五十二年 남송이 왕을 책봉하다 (464)

五十四年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (466)

五十五年春三月 북위가 후궁으로 들일 왕녀를 요구하다 (467)

五十六年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (468)

五十七年春二月 신라의 실직주성을 빼앗다 (469)

五十七年夏四月 북위에 조공하다 (469)

五十八年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (470)

五十八年秋八月 백제가 침입하다 (470)

五十九年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (471)

五十九年秋九月 백성 노구 등이 북위로 달아나다 (471)

六十年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (472)

六十年秋七月 북위에 조공하다 (472)

六十一年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (473)

六十一年秋八月 북위에 조공하다 (473)

六十二年春三月 북위에 조공하다 (474)

六十二年秋七月 북위와 남송에 조공하다 (474)

六十三年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (475)

六十三年秋八月 북위에 조공하다 (475)

六十三年秋九月 백제 한성을 함락하다 (475)

六十四年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (476)

六十四年秋七月 북위에 조공하다

六十四年秋九月 북위에 조공하다

六十五年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (477)

六十五年秋九月 북위에 조공하다

六十六年 남송에 조공하다 (478)

六十七年 백제의 연신이 투항하다 (479)

六十八年春三月 북위에 조공하다 (480)

481-491 : 공백

《삼국사기》에 기록된 장수왕의 내정 관련 기록의 거의 전부[24]로, 나머지는 거의 대부분이 북위와 남조에 조공한 기사들이다. 북위에 조공기록만 25회. 기록의 반이 북위 조공기록이다. 덕분에 일부 역사애호가들 사이에서 조공왕이라는 괴랄한 별명도 있다.

이 부분에서 김부식의 사대 정책이 드러나는 거 아니냐는 주장도 간혹 나오는데, 그보다는 고구려 멸망 이후 고구려에 대한 기록이 심히 부실한 것이 문제였다. 그래서 글자수라도 채우기 위해 중국 사서 내용을 옮겨 적었어야 했다. 이럴 수 밖에 없는 것이 삼국사기는 거의 천 년쯤 뒤에 쓴 책이고, 고구려와 발해가 멸망하고나서는 후기 고구려와 관련된 사료 대다수가 소실되어 남아있는 자료가 많지 않았다. 이 때문에 국내 기록이 부족하면, 《삼국사기》에서는 당연하게 중국 사서의 기록을 모아서 내용을 채웠다. 당연히 중국 사서에 기록되어 있는 장수왕 관련 기사야 조공으로 기록된 외교 기사만 있을 수 밖에.

신집 5권을 인용한 것으로 추정되는 고국원왕 대까지[25]의 기록은 그럭저럭 있고, 광개토대왕은 광개토대왕릉비의 존재 때문에 기록이 어느 정도 받쳐주는데, 장수왕 대 기록부터는 전적으로 중국 기록에 의존해야 했다.

을지문덕, 연개소문과 관련된 기록을 보더라도 《삼국사기》 편찬 당시에 고구려 기록이 없어서 김부식이 골머리를 싸맨 기록이 남아있으며, 민간에서 주도해 만든 《삼국유사》의 경우에도 신라의 기록에 비해 고구려, 백제의 기록은 심히 부족하다.

또한 전근대 시대 중국과의 조공 관계는 국제 외교로써, 굳이 쓸데없는 위축감 가질 필요가 전혀 없다. 그냥 조공 = 외교를 활발히 한 것이다. 오히려 이 당시엔 조공국이 책봉국을 선택할 수 있는 아이러니도 있었고, 2개국 이상의 책봉을 받기도 했다. 책봉국도 조공국을 늘리려는데만 관심 가졌지, 조공국이 적국의 책봉을 받건 말건 별 신경을 쓰지 않았다.[26] 그러니 이 당시 책봉 - 조공 관계는, 그냥 중소 국가나 지역 강국이 강대국들이랑 친하게 지낸 것 정도의 수준이라고 보면 될 듯하다.

(자료 : 장수왕(413-491), 나무위키)

1. 413 -420 시기

一年冬十月 장수왕이 즉위하다 (413)

二年 동진이 왕을 책봉하다 (414)

三年秋八月 이상한 새가 왕궁에 모이다 (415)

三年冬十月 흰 노루를 사냥하다 (415)

三年冬十二月 국내성에 많은 눈이 내리다 (415)

416-419 : 공백 (4년)

八年夏五月 나라 동쪽에 홍수가 나다 (420)

** Charaton (412 - 420 ?)

Charaton (Olympiodorus of Thebes: Χαράτων) was one of the first kings of the Huns.

In end of 412 or beginning of 413, Charaton received the Byzantine ambassador Olympiodorus sent by Honorius.[1] Olympiodorus travelled to Charaton’s kingdom by sea, but does not record whether the sea in question was the Black Sea or the Adriatic Sea. As the History deals exclusively with the Western Roman Empire, it was probably the Adriatic, and visited them somewhere in Pannonian Basin.[2] Olympiodorus recounts;

"Donatus and the Huns, and the skillfulness of their kings in shooting with the bow. The author relates that he himself was sent on a mission to them and Donatus, and gives a tragic account of his wanderings and perils by the sea. How Donatus, being deceived by an oath, was unlawfully put to death. How Charaton, the first of the kings, being incensed by the murder, was appeased by presents from the emperor."[3]

Although some scholars such as E. A. Thompson and Hyun Jin Kim have read Donatus as being a previous ruler,[4][5] others, such as Franz Altheim and Otto Maenchen-Helfen reject this assumption.[1] Maenchen-Helfen argues that the name Donatus was common in the Roman Empire and that Donatus may have been a Roman who fled the empire to live with the Huns, as others are known to have done.[6]

Etymology

The name is found in Greek as Χαράτων (Kharatōn). Otto J. Maenchen-Helfen notes that the -ton element might be an artifact of the Greek transcription, and the name may actually have ended in -tom, -ton, -to, -ta, or -t.[7]

Omeljan Pritsak, following an earlier suggestion by A. Vámbéry, derived the root Chara- from Altaic xara - qara, with the meaning of "black" and "great; northern".[8] He derived the second part -ton from a Saka loanword into Turkic, thauna > *taun > tōn, "garment, clothing, mantel".[8] Pritsak concluded that the name Qara-Ton (black clad; with black coat) was an intentionally cryptic term for horse, possibly related to Hunnic totemism.[9]

Maenchen-Helfen noted that the above proposal is "phonetically sound", but questioned whether the word ton had been loaned into Turkic in the fifth century.[7] He suggests that if Charaton did in fact mean "black coat", then it could have been the name of Charaton's clan or tribe rather than his personal name; he compares the Kyrgyz tribal name Bozton (Gray Coats).[10]

F. Altheim suggested that the name is a title from *qara-tun, meaning "black people", with black referencing the direction north.[11]

Maenchen-Helfen also suggests an Iranian etymology as an potential alternative, with chara- deriving from a word akin to Parthian hara, xara (dark), as in the Parthian name Charaspes.[12] He further notes that the -ton element is also found in the Scythian name Sardonius and the Ossetian name Syrdon.[12]

(source : Charaton, Wikipedia)

2. 420-435 시기

八年夏五月 나라 동쪽에 홍수가 나다 (420)

421-424 : 공백 (4년)

十三年春二月 신라가 사신을 보내다 (425)

十三年秋九月 풍년이 들어 왕이 잔치를 베풀다 (425)

十四年 북위에 사신을 보내 조공하다 (426)

十五年 평양성으로 천도하다 (427)

428-435 : 공백 (8년)

** Octar (420-430, Western Huns) - brother of Mundzuk

Octar or Ouptaros was a Hunnic ruler. He ruled along brother Rugila according to Jordanes in Getica, "...Mundzucus, whose brothers were Octar and Ruas, who were supposed to have been kings before Attila, although not altogether of the same [territories] as he".[1] Their brother Mundzuk was father of Attila, but he was not a supreme ruler of the Huns.[1] According to Priscus their fourth brother Oebarsius was still alive in 448 AD.[1] Their ancestors and relation with previous rulers Uldin and Charaton are unknown.[2]

Similar dual kingship, possibly a geographical division where Rugila ruled over Eastern Huns while Octar over Western Huns, had Attila and Bleda.[3]

Octar, identified with Ouptaros, according to Socrates of Constantinople died in 430 near Rhine, "For the king of the Huns, Uptaros by name, having burst asunder in the night from surfeit, the Burgundians attacked that [the Huns of Uptaros] people then without a leader; and although few in numbers and their opponents many, they obtained victory".[4]

Etymology

The name is recorded in two variants, Greek Ούπταρος (Ouptaros), and Latin Octar.[5] The change from -ct- to -pt- is characteristic of Balkan Latin.[5][6] Otto J. Maenchen-Helfen considered the name to be of unknown origin.[7] Omeljan Pritsak derived the name from Turkic-Mongolian word *öktem (strong, brave, imperious; proud, boastful; pride) and verb ökte- / oktä- (to encourage).[5] He argued that the deverbal Turkic-Mongolian suffix m was replaced in Turkic by z while in Mongolian by ri.[5] The reconstructed form is appellative *öktä-r.[5]

(source : Octar (420-430), Wikipedia)

** Rugila (420-430 Eastern Huns, 430-435)- Brother of Mundzuk

Rugila or Ruga (also Ruas; died second half of the 430s AD),[1] was a ruler who was a major factor in the Huns' early victories over the Roman Empire. He served as an important forerunner with his brother Octar, with whom he initially ruled in dual kingship, possibly a geographical division where Rugila ruled over Eastern Huns while Octar over Western Huns,[2] during the 5th century AD.

Etymology

The name is mentioned in three variants, Ρούγας (Rougas), Ρουας (Rouas), and Ρωίλας (Roilas).[3] Common spellings are Ruga, Roas, Rugila.[4][3][5] Otto Maenchen-Helfen included this name among those of Germanic or Germanized origin, but without any derivation, only comparison with Rugemirus and Rugolf.[4] Denis Sinor considered a name with initial r- not of Altaic origin (example Ragnaris).[6]

Omeljan Pritsak derived it from Old Turkic and considered it to be of composite form, with the change ουγα- > ουα, Greek suffix -ς, and those with ila as Gothicized variant.[3] The Ancient Greek Ρ (Rho) rendered Hunnic *hr-, which is Old Turkic *her > har/ar/er (man), common component of names and titles.[3] Second part ουγα- or ουα resembles Old Turkic title ogä (to think).[7] Thus the reconstruction goes *hēr ögä > *hər ögä > hrögä.[8]

History

Initially Rugila had ruled together with his brother Octar, who died in 430 during a military campaign against the Burgundians.[9] In 432, Rugila is mentioned as a sole ruler of the Huns.[10] According to Prosper of Aquitaine, "After the loss of his office, Aetius lived on his estate. When there some of his enemies by an unexpected attack attempted to seize him, he fled to Rome, and from there to Dalmatia. By the way of Pannonia, he reached the Huns. Through their friendship and help he obtained peace with the rulers and was reinstated in his old office. [] Ruga was ruler of the gens Chunorum".[11] Priscus recounts "in the land of the Paeonians on the river Sava, which according to the treaty of Aetius, general of the Western Romans, belonged to the barbarian", some scholars explain this as meaning that Aetius ceded part of Pannonia Prima to Ruga.[12] Scholars date this cession to 425, 431, or 433.[12] Maenchen-Helfen considered that the area was ceded to Attila.[12]

In 422, there was a major Hunnic incursion into Thracia launched from Danube, menacing even Constantinople, which ended with a peace treaty by which Romans had to pay annually 350 pounds of gold.[13] In 432-433, some tribes from Hunnic confederation on the Danube fled to Roman territory and service of Theodosius II.[5][14] Rugila demanded through his experienced diplomat Esla (Ήσλα, Turkic és-lä, "the great, old"; later also served Attila[15]) return of all fugitives, otherwise the peace will be terminated, but soon died and was succeeded by sons of his brother Mundzuk, Bleda and Attila, who became joint rulers of the united Hunnic tribes.[14][16][17]

The Eastern Roman politician Plinta along quaestor Epigenes nevertheless had to go for adverse negotiations at Margus; according to Priscus, it included trade agreement, the annual tribute was raised to 700 pounds of gold, and fugitives were surrendered, among whom two of royal descent, Mamas (Μάμα, Christian name[18]) and Atakam (Άτακάμ, Turkic-Altaic ata-qām, "father pagan, priest"[18]) probably because of conversion to Christianity,[19] were crucified by the Huns at Carso (Hârșova).[20][16]

According to Socrates of Constantinople, Theodosius II prayed to God and managed to obtain what he sought - Ruga was struck dead by a thunderbolt, and among his men followed plague, and fire came down from the heaven consuming his survivors. This text is panegyric on Theodosius II, and happened shortly after 425 AD.[21] Similarly, Theodoret recounts that God helped Theodosius II because he issued a law that ordered destruction of all pagan temples, and Ruga's death was the abundant harvest that followed these good seeds.[21] However, the edict was issued on November 14, 435 AD, so Ruga died after that date.[21] Chronica Gallica of 452 places his death in 434, "Aetius is restored to favor. Rugila, king of the Huns, with whom peace was made, dies. Bleda succeeds him".[22]

(source : Rugila (420-430 easter Huns, 430-435), Wikipedia)

** Mundzuk - father of Attila

Mundzuk was a Hunnic chieftain, brother of the Hunnic rulers Octar and Rugila, and father of Bleda and Atilla. Jordanes in Getica recounts "For this Attila was the son of Mundzucus, whose brothers were Octar and Ruas, who were supposed to have been kings before Attila, although not altogether of the same [territories] as he".[1]

Etymology

The name is recorded as Mundzucus by Jordanes, Mundiucus by Cassiodorus, Μουνδίουχος (Moundioukhos) by Priscus, and Μουνδίου (Moundiou) by Theophanes of Byzantium.[2][3] Gyula Németh and László Rásonyi argued that the name is a transcription of Turkic munčuq, munʒuq, minʒaq, bunčuq, bonʒuq, mončuq, with the potential meanings of "jewel, pearl, bead" or "flag".[4][5]

Legacy

Known as Bendegúz in Hungarian,[6] he appears in Hungary's national anthem as an ancestor of the Hungarians.[7] The name is also present in Croatian, forming the surname Mandžukić.

(source : Mundzuk, Wikipedia)

3. 435-445 시기

428-435 : 공백 (8년)

二十四年夏六月 북위에 조공하니 북위가 책봉하다 (436)

二十四年 북연 왕 풍홍이 도움을 요청하다 (436)

二十五年 북위가 북연을 토벌할 것임을 알려오다 (437)

二十五年夏四月 북연의 화룡성을 점령하다 (437)

二十五年夏五月 북연 왕 풍홍을 데려오다 (437)

二十六年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (438)

二十七年春三月 북연 왕 풍홍을 죽이다 (439)

二十八年冬十一月 북위에 조공하다 (440)

二十八年冬十二月 북위에 조공하다 (440)

二十九年 신라가 변방의 장수를 죽이다 (441)

442 -454 : 공백 (13년)

** Bleda (435-445) - Brother of Attila

Bleda

Bleda (/ˈblɛdə, ˈbleɪdə/) was a Hunnic ruler, the brother of Attila the Hun.[1]

As nephews to Rugila, Attila and his elder brother Bleda succeeded him to the throne. Bleda's reign lasted for eleven years until his death. While it has been speculated by Jordanes that Attila murdered him on a hunting trip,[2] it is unknown exactly how he died. However, there is an alternative theory that Bleda attempted to kill Attila on a hunting trip, but Attila being a skilled warrior defeated Bleda.[citation needed] one of the few things known about Bleda is that, after the great Hun campaign of 441, he acquired a Moorish dwarf named Zerco. Bleda was highly amused by Zerco and went so far as to make a suit of armor for the dwarf so that Zerco could accompany him on campaign.

Etymology

Greek sources have Βλήδας and Βλέδας (Bledas), Chronicon Paschale Βλίδας (Blidas),[3] and Latin Bleda.[4]

Otto Maenchen-Helfen considered the name to be of Germanic or Germanized origin, a short form of Bladardus, Blatgildus, Blatgisus.[5] Denis Sinor considered that the name begins with consonant cluster, and as such it cannot be of Altaic origin.[6] In 455 is recorded the Arian bishop Bleda along Genseric and the Vandals,[7][8] and one of Totila generals also had the same name.[5]

Omeljan Pritsak considered its root bli- had typical vocalic metathesis of Oghur-Bulgar language from < *bil-, which is Old Turkic "to know".[3] Thus Hunnic *bildä > blidä was actually Old Turkic bilgä (wise, sovereign).[3]

** Bleda and Attila's rule

By 432, the Huns were united under Rugila. His death in 434 left his nephews Attila and Bleda (the sons of his brother Mundzuk) in control over all the united Hun tribes. At the time of their accession, the Huns were bargaining with Byzantine emperor Theodosius II's envoys over the return of several renegade tribes who had taken refuge within the Roman Empire. The following year, Attila and Bleda met with the imperial legation at Margus (present-day Požarevac) and, all seated on horseback in the Hunnic manner, negotiated a successful treaty: the Romans agreed not only to return the fugitive tribes (who had been a welcome aid against the Vandals), but also to double their previous tribute of 350 Roman pounds (ca. 114.5 kg) of gold, open their markets to Hunnish traders, and pay a ransom of eight solidi for each Roman taken prisoner by the Huns. The Huns, satisfied with the treaty, decamped from the empire and returned to their home, perhaps to consolidate and strengthen their empire. Theodosius used this opportunity to strengthen the walls of Constantinople, building the city's first sea wall, and to build up his border defenses along the Danube.

For the next five years, the Huns stayed out of Roman sight as they tried to invade the Persian Empire. A crushing defeat in Armenia caused them to abandon this attempt and return their attentions to Europe. In 440, they reappeared on the borders of the Roman Empire, attacking the merchants at the market on the north bank of the Danube that had been established by the treaty. Attila and Bleda threatened further war, claiming that the Romans had failed to fulfill their treaty obligations and that the Bishop of Margus had crossed the Danube to ransack and desecrate the royal Hun graves on the Danube's north bank. They crossed the Danube and laid waste to Illyrian cities and forts on the river, among them, according to Priscus, Viminacium (present-day Kostolac), which was a city of the Moesians in Illyria. Their advance began at Margus, for when the Romans discussed handing over the offending bishop, he slipped away secretly to the Huns and betrayed the city to them.

Theodosius had stripped the river's defenses in response to the Vandal Gaiseric's capture of Carthage in 440 and the Sassanid Yazdegerd II's invasion of Armenia in 441. This left Attila and Bleda a clear path through Illyria into the Balkans, which they invaded in 441. The Hunnish army, having sacked Margus and Viminacium, took Singidunum (modern Belgrade) and Sirmium (modern Sremska Mitrovica) before halting. A lull followed in 442, and, during this time, Theodosius recalled his troops from North Africa and ordered a large new issue of coins to finance operations against the Huns. Having made these preparations, he thought it safe to refuse the Hunnish kings' demands.

Attila and Bleda responded by renewing their campaign in 443. Striking along the Danube, they overran the military centers of Ratiaria and successfully besieged Naissus (modern Niš) with battering rams and rolling towers (military sophistication that was new to the Hun repertory), then, pushing along the Nišava, they took Serdica (Sofia), Philippopolis (Plovdiv) and Arcadiopolis (Luleburgaz). They encountered and destroyed the Roman force outside Constantinople and were only halted by their lack of siege equipment capable of breaching the city's massive walls. Theodosius admitted defeat and sent the court official Anatolius to negotiate peace terms, which were harsher than the previous treaty: the Emperor agreed to hand over 6,000 Roman pounds (ca. 1,963 kg) of gold as punishment for having disobeyed the terms of the treaty during the invasion; the yearly tribute was tripled, rising to 2,100 Roman pounds (ca. 687 kg) in gold; and the ransom for each Roman prisoner rose to twelve solidi.

Their demands met for a time, the Hun kings withdrew into the interior of their empire. According to Jordanes (following Priscus), sometime during the peace following the Huns' withdrawal from Byzantium (probably around 445), Bleda died (killed by his brother, according to the classical sources), and Attila took the throne for himself. A few sources indicate that Bleda tried to kill Attila first, to which Attila retaliated.

In 448, Priscus encountered Bleda's widow, then governor of an unnamed village, while on an embassy to Attila's court.

(source : Bleda (434-445), Wikipedia)

4. 436-455 시기

二十四年夏六月 북위에 조공하니 북위가 책봉하다 (436)

二十四年 북연 왕 풍홍이 도움을 요청하다 (436)

二十五年 북위가 북연을 토벌할 것임을 알려오다 (437)

二十五年夏四月 북연의 화룡성을 점령하다 (437)

二十五年夏五月 북연 왕 풍홍을 데려오다 (437)

二十六年春二月 북위에 조공하다 (438)

二十七年春三月 북연 왕 풍홍을 죽이다 (439)

二十八年冬十一月 북위에 조공하다 (440)

二十八年冬十二月 북위에 조공하다 (440)

二十九年 신라가 변방의 장수를 죽이다 (441)

442 -454 : 공백 (13년)

** Attila (406-453, r 434-453)

Attila

Attila (/ˈætɪlə, əˈtɪlə/; fl. c. 406–453), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns from 434 until his death in March 453. He was also the leader of a tribal empire consisting of Huns, Ostrogoths, and Alans among others, in Central and Eastern Europe.

During his reign, he was one of the most feared enemies of the Western and Eastern Roman Empires. He crossed the Danube twice and plundered the Balkans, but was unable to take Constantinople. His unsuccessful campaign in Persia was followed in 441 by an invasion of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, the success of which emboldened Attila to invade the West.[3] He also attempted to conquer Roman Gaul (modern France), crossing the Rhine in 451 and marching as far as Aurelianum (Orléans) before being defeated at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains.

He subsequently invaded Italy, devastating the northern provinces, but was unable to take Rome. He planned for further campaigns against the Romans, but died in 453. After Attila's death, his close adviser, Ardaric of the Gepids, led a Germanic revolt against Hunnic rule, after which the Hunnic Empire quickly collapsed.

Appearance and character

There is no surviving first-hand account of Attila's appearance, but there is a possible second-hand source provided by Jordanes, who cites a description given by Priscus.[4][5]

He was a man born into the world to shake the nations, the scourge of all lands, who in some way terrified all mankind by the dreadful rumors noised abroad concerning him. He was haughty in his walk, rolling his eyes hither and thither, so that the power of his proud spirit appeared in the movement of his body. He was indeed a lover of war, yet restrained in action, mighty in counsel, gracious to suppliants and lenient to those who were once received into his protection. Short of stature, with a broad chest and a large head; his eyes were small, his beard thin and sprinkled with grey; and he had a flat nose and tanned skin, showing evidence of his origin.[6]:182–183

Some scholars have suggested that this description is typically East Asian, because it has all the combined features that fit the physical type of people from Eastern Asia, and Attila's ancestors may have come from there.[5][7]:202 Other historians also believed that the same descriptions were also evident on some Scythian people.[8][9]

Etymology

Many scholars have argued that Attila derives from East Germanic origin; Attila is formed from the Gothic or Gepidic noun atta, "father", by means of the diminutive suffix -ila, meaning "little father".[10]:386[11]:29[12]:46 The Gothic etymology was first proposed by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in the early 19th century.[13]:211 Maenchen-Helfen notes that this derivation of the name "offers neither phonetic nor semantic difficulties",[10]:386 and Gerhard Doerfer notes that the name is simply correct Gothic.[11]:29 The name has sometimes been interpreted as a Germanization of a name of Hunnic origin.[11]:29-32

Other scholars have argued for a Turkic origin of the name. Omeljan Pritsak considered Ἀττίλα (Attíla) a composite title-name which derived from Turkic *es (great, old), and *t il (sea, ocean), and the suffix /a/.[14]:444 The stressed back syllabic til assimilated the front member es, so it became *as.[14]:444 It is a nominative, in form of attíl- (< *etsíl < *es tíl) with the meaning "the oceanic, universal ruler".[14]:444 J.J. Mikkola connected it with Turkic āt (name, fame).[13]:216 As another Turkic possibility, H. Althof (1902) considered it was related to Turkish atli (horseman, cavalier), or Turkish at (horse) and dil (tongue).[13]:216 Maenchen-Helfen argues that Pritsak's derivation is "ingenious but for many reasons unacceptable",[10]:387 while dismissing Mikkola's as "too farfetched to be taken seriously".[10]:390 M. Snædal similarly notes that none of these proposals has achieved wide acceptance.[13]:215-216 Criticizing the proposals of finding Turkic or other etymologies for Attila, Doerfer notes that King George VI of England had a name of Greek origin, and Süleyman the Magnificent had a name of Arabic origin, yet that does not make them Greeks or Arabs: it is therefore plausible that Attila would have a name not of Hunnic origin.[11]:31-32 Historian Hyun Jin Kim, however, has argued that the Turkic etymology is "more probable".[15]:30

M. Snædal, in a paper that rejects the Germanic derivation but notes the problems with the existing proposed Turkic etymologies, argues that Attila's name could have originated from Turkic-Mongolian at, adyy/agta (gelding, warhorse) and Turkish atli (horseman, cavalier), meaning "possessor of geldings, provider of warhorses".[13]:216-217

Historiography and source

The historiography of Attila is faced with a major challenge, in that the only complete sources are written in Greek and Latin by the enemies of the Huns. Attila's contemporaries left many testimonials of his life, but only fragments of these remain.[16]:25 Priscus was a Byzantine diplomat and historian who wrote in Greek, and he was both a witness to and an actor in the story of Attila, as a member of the embassy of Theodosius II at the Hunnic court in 449. He was obviously biased by his political position, but his writing is a major source for information on the life of Attila, and he is the only person known to have recorded a physical description of him. He wrote a history of the late Roman Empire in eight books covering the period from 430 to 476.[17]

Today we have only fragments of Priscus' work, but it was cited extensively by 6th-century historians Procopius and Jordanes,[18]:413 especially in Jordanes' The Origin and Deeds of the Goths. It contains numerous references to Priscus's history, and it is also an important source of information about the Hunnic empire and its neighbors. He describes the legacy of Attila and the Hunnic people for a century after Attila's death. Marcellinus Comes, a chancellor of Justinian during the same era, also describes the relations between the Huns and the Eastern Roman Empire.[16]:30

Numerous ecclesiastical writings contain useful but scattered information, sometimes difficult to authenticate or distorted by years of hand-copying between the 6th and 17th centuries. The Hungarian writers of the 12th century wished to portray the Huns in a positive light as their glorious ancestors, and so repressed certain historical elements and added their own legends.[16]:32

The literature and knowledge of the Huns themselves was transmitted orally, by means of epics and chanted poems that were handed down from generation to generation.[18]:354 Indirectly, fragments of this oral historyhave reached us via the literature of the Scandinavians and Germans, neighbors of the Huns who wrote between the 9th and 13th centuries. Attila is a major character in many Medieval epics, such as the Nibelungenlied, as well as various Eddas and sagas.[16]:32[18]:354

Archaeological investigation has uncovered some details about the lifestyle, art, and warfare of the Huns. There are a few traces of battles and sieges, but today the tomb of Attila and the location of his capital have not yet been found.[16]:33–37

Early life and background

The Huns were a group of Eurasian nomads, appearing from east of the Volga, who migrated further into Western Europe c. 370[19] and built up an enormous empire there. Their main military techniques were mounted archery and javelin throwing. They were in the process of developing settlements before their arrival in Western Europe, yet the Huns were a society of pastoral warriors[18]:259 whose primary form of nourishment was meat and milk, products of their herds.

The origin and language of the Huns has been the subject of debate for centuries. According to some theories, their leaders at least may have spoken a Turkic language, perhaps closest to the modern Chuvash language.[14]:444 One scholar suggests a relationship to Yeniseian.[20] According to the Encyclopedia of European Peoples, "the Huns, especially those who migrated to the west, may have been a combination of central Asian Turkic, Mongolic, and Ugric stocks".[21]

Attila's father Mundzuk was the brother of kings Octar and Ruga, who reigned jointly over the Hunnic empire in the early fifth century. This form of diarchy was recurrent with the Huns, but historians are unsure whether it was institutionalized, merely customary, or an occasional occurrence.[16]:80 His family was from a noble lineage, but it is uncertain whether they constituted a royal dynasty. Attila's birthdate is debated; journalist Éric Deschodt and writer Herman Schreiber have proposed a date of 395.[22][23] However, historian Iaroslav Lebedynsky and archaeologist Katalin Escher prefer an estimate between the 390s and the first decade of the fifth century.[16]:40Several historians have proposed 406 as the date.[1]:92[2]:202

Attila grew up in a rapidly changing world. His people were nomads who had only recently arrived in Europe.[24] They crossed the Volga river during the 370s and annexed the territory of the Alans, then attacked the Gothic kingdom between the Carpathian mountains and the Danube. They were a very mobile people, whose mounted archers had acquired a reputation for invincibility, and the Germanic tribes seemed unable to withstand them.[18]:133–151 Vast populations fleeing the Huns moved from Germania into the Roman Empire in the west and south, and along the banks of the Rhine and Danube. In 376, the Goths crossed the Danube, initially submitting to the Romans but soon rebelling against Emperor Valens, whom they killed in the Battle of Adrianople in 378.[18]:100 Large numbers of Vandals, Alans, Suebi, and Burgundians crossed the Rhine and invaded Roman Gaul on December 31, 406 to escape the Huns.[16]:233 The Roman Empire had been split in half since 395 and was ruled by two distinct governments, one based in Ravenna in the West, and the other in Constantinople in the East. The Roman Emperors, both East and West, were generally from the Theodosian family in Attila's lifetime (despite several power struggles).[25]:13

The Huns dominated a vast territory with nebulous borders determined by the will of a constellation of ethnically varied peoples. Some were assimilated to Hunnic nationality, whereas many retained their own identities and rulers but acknowledged the suzerainty of the king of the Huns.[25]:11 The Huns were also the indirect source of many of the Romans' problems, driving various Germanic tribes into Roman territory, yet relations between the two empires were cordial: the Romans used the Huns as mercenaries against the Germans and even in their civil wars. Thus, the usurper Joannes was able to recruit thousands of Huns for his army against Valentinian III in 424. It was Aëtius, later Patrician of the West, who managed this operation. They exchanged ambassadors and hostages, the alliance lasting from 401 to 450 and permitting the Romans numerous military victories.[18]:111 The Huns considered the Romans to be paying them tribute, whereas the Romans preferred to view this as payment for services rendered. The Huns had become a great power by the time that Attila came of age during the reign of his uncle Ruga, to the point that Nestorius, the Patriarch of Constantinople, deplored the situation with these words: "They have become both masters and slaves of the Romans".[18]:128

Campaigns against the Eastern Roman Empire

The Empire of the Huns and subject tribes at the time of Attila

Empire of Attila the Hun AD 450

The death of Rugila (also known as Rua or Ruga) in 434 left the sons of his brother Mundzuk, Attila and Bleda, in control of the united Hun tribes. At the time of the two brothers' accession, the Hun tribes were bargaining with Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II's envoys for the return of several renegades who had taken refuge within the Eastern Roman Empire, possibly Hunnic nobles who disagreed with the brothers' assumption of leadership.

The following year (435), Attila and Bleda met with the imperial legation at Margus (Požarevac), all seated on horseback in the Hunnic manner,[26] and negotiated an advantageous treaty. The Romans agreed to return the fugitives, to double their previous tribute of 350 Roman pounds (c. 115 kg) of gold, to open their markets to Hunnish traders, and to pay a ransom of eight solidi for each Roman taken prisoner by the Huns. The Huns, satisfied with the treaty, decamped from the Roman Empire and returned to their home in the Great Hungarian Plain, perhaps to consolidate and strengthen their empire. Theodosius used this opportunity to strengthen the walls of Constantinople, building the city's first sea wall, and to build up his border defenses along the Danube.

The Huns remained out of Roman sight for the next few years (436-440?) while they invaded the Sassanid Empire. They were defeated in Armenia by the Sassanids, abandoned their invasion, and turned their attentions back to Europe. In 440, they reappeared in force on the borders of the Roman Empire, attacking the merchants at the market on the north bank of the Danube that had been established by the treaty.

Crossing the Danube, they laid waste to the cities of Illyricum and forts on the river, including (according to Priscus) Viminacium, a city of Moesia. Their advance began at Margus, where they demanded that the Romans turn over a bishop who had retained property that Attila regarded as his. While the Romans discussed the bishop's fate, he slipped away secretly to the Huns and betrayed the city to them.

While the Huns attacked city-states along the Danube, the Vandals (led by Geiseric) captured the Western Roman province of Africa and its capital of Carthage. Carthage was the richest province of the Western Empire and a main source of food for Rome.

The Sassanid Shah Yazdegerd II invaded Armenia in 441.

The Romans stripped the Balkan area of forces, sending them to Sicily in order to mount an expedition against the Vandals in Africa. This left Attila and Bleda a clear path through Illyricum into the Balkans, which they invaded in 441. The Hunnish army sacked Margus and Viminacium, and then took Singidunum (Belgrade) and Sirmium. During 442, Theodosius recalled his troops from Sicily and ordered a large issue of new coins to finance operations against the Huns. He believed that he could defeat the Huns and refused the Hunnish kings' demands.

Attila responded with a campaign in 443.[27] The Huns were equipped with new military weapons as they advanced along the Danube, such as battering rams and rolling siege towers, and they overran the military centers of Ratiara and successfully besieged Naissus (Niš).

Advancing along the Nišava River, the Huns next took Serdica (Sofia), Philippopolis (Plovdiv), and Arcadiopolis (Lüleburgaz). They encountered and destroyed a Roman army outside Constantinople but were stopped by the double walls of the Eastern capital. They defeated a second army near Callipolis (Gelibolu).

Theodosius, stripped of his armed forces, admitted defeat, sending the Magister militum per Orientem Anatolius to negotiate peace terms. The terms were harsher than the previous treaty: the Emperor agreed to hand over 6,000 Roman pounds (c. 2000 kg) of gold as punishment for having disobeyed the terms of the treaty during the invasion; the yearly tribute was tripled, rising to 2,100 Roman pounds (c. 700 kg) in gold; and the ransom for each Roman prisoner rose to 12 solidi.

Their demands were met for a time, and the Hun kings withdrew into the interior of their empire. Bleda died following the Huns' withdrawal from Byzantium (probably around 445). Attila then took the throne for himself, becoming the sole ruler of the Huns.[28]

Solitary kingship

In 447, Attila again rode south into the Eastern Roman Empire through Moesia. The Roman army, under Gothic magister militum Arnegisclus, met him in the Battle of the Utus and was defeated, though not without inflicting heavy losses. The Huns were left unopposed and rampaged through the Balkans as far as Thermopylae.

Constantinople itself was saved by the Isaurian troops of magister militum per Orientem Zeno and protected by the intervention of prefect Constantinus, who organized the reconstruction of the walls that had been previously damaged by earthquakes and, in some places, to construct a new line of fortification in front of the old. An account of this invasion survives:

The barbarian nation of the Huns, which was in Thrace, became so great that more than a hundred cities were captured and Constantinople almost came into danger and most men fled from it. ... And there were so many murders and blood-lettings that the dead could not be numbered. Ay, for they took captive the churches and monasteries and slew the monks and maidens in great numbers.— Callinicus, in his Life of Saint Hypatius

In the west

The general path of the Hun forces in the invasion of Gaul

In 450, Attila proclaimed his intent to attack the Visigoth kingdom of Toulouse by making an alliance with Emperor Valentinian III. He had previously been on good terms with the Western Roman Empire and its influential general Flavius Aëtius. Aëtius had spent a brief exile among the Huns in 433, and the troops that Attila provided against the Goths and Bagaudae had helped earn him the largely honorary title of magister militum in the west. The gifts and diplomatic efforts of Geiseric, who opposed and feared the Visigoths, may also have influenced Attila's plans.

However, Valentinian's sister was Honoria, who had sent the Hunnish king a plea for help—and her engagement ring—in order to escape her forced betrothal to a Roman senator in the spring of 450. Honoria may not have intended a proposal of marriage, but Attila chose to interpret her message as such. He accepted, asking for half of the western Empire as dowry.

When Valentinian discovered the plan, only the influence of his mother Galla Placidia convinced him to exile Honoria, rather than killing her. He also wrote to Attila, strenuously denying the legitimacy of the supposed marriage proposal. Attila sent an emissary to Ravenna to proclaim that Honoria was innocent, that the proposal had been legitimate, and that he would come to claim what was rightfully his.

Attila interfered in a succession struggle after the death of a Frankish ruler. Attila supported the elder son, while Aëtius supported the younger. (The location and identity of these kings is not known and subject to conjecture.) Attila gathered his vassals—Gepids, Ostrogoths, Rugians, Scirians, Heruls, Thuringians, Alans, Burgundians, among others–and began his march west. In 451, he arrived in Belgica with an army exaggerated by Jordanes to half a million strong.

On April 7, he captured Metz. Other cities attacked can be determined by the hagiographic vitae written to commemorate their bishops: Nicasius was slaughtered before the altar of his church in Rheims; Servatus is alleged to have saved Tongeren with his prayers, as Saint Genevieve is said to have saved Paris.[29] Lupus, bishop of Troyes, is also credited with saving his city by meeting Attila in person.[3][30]

Aëtius moved to oppose Attila, gathering troops from among the Franks, the Burgundians, and the Celts. A mission by Avitus and Attila's continued westward advance convinced the Visigoth king Theodoric I(Theodorid) to ally with the Romans. The combined armies reached Orléans ahead of Attila, thus checking and turning back the Hunnish advance. Aëtius gave chase and caught the Huns at a place usually assumed to be near Catalaunum (modern Châlons-en-Champagne). Attila decided to fight the Romans on plains where he could use his cavalry.[31]

The two armies clashed in the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, the outcome of which is commonly considered to be a strategic victory for the Visigothic-Roman alliance. Theodoric was killed in the fighting, and Aëtius failed to press his advantage, according to Edward Gibbon and Edward Creasy, because he feared the consequences of an overwhelming Visigothic triumph as much as he did a defeat. From Aëtius' point of view, the best outcome was what occurred: Theodoric died, Attila was in retreat and disarray, and the Romans had the benefit of appearing victorious.

Invasion of Italy and death

Raphael's The Meeting between Leo the Great and Attila depicts Leo, escorted by Saint Peter and Saint Paul, meeting with the Hun emperor outside Rome.

Attila returned in 452 to renew his marriage claim with Honoria, invading and ravaging Italy along the way. Communities became established in what would later become Venice as a result of these attacks when the residents fled to small islands in the Venetian Lagoon. His army sacked numerous cities and razed Aquileiaso completely that it was afterwards hard to recognize its original site.[32]:159 Aëtius lacked the strength to offer battle, but managed to harass and slow Attila's advance with only a shadow force. Attila finally halted at the River Po. By this point, disease and starvation may have taken hold in Attila's camp, thus helping to stop his invasion.[citation needed]

Emperor Valentinian III sent three envoys, the high civilian officers Gennadius Avienus and Trigetius, as well as the Bishop of Rome Leo I, who met Attila at Mincio in the vicinity of Mantua and obtained from him the promise that he would withdraw from Italy and negotiate peace with the Emperor.[33] Prosper of Aquitaine gives a short description of the historic meeting, but gives all the credit to Leo for the successful negotiation. Priscus reports that superstitious fear of the fate of Alaric gave him pause—as Alaric died shortly after sacking Rome in 410.

Italy had suffered from a terrible famine in 451 and her crops were faring little better in 452. Attila's devastating invasion of the plains of northern Italy this year did not improve the harvest.[32]:161 To advance on Rome would have required supplies which were not available in Italy, and taking the city would not have improved Attila's supply situation. Therefore, it was more profitable for Attila to conclude peace and retreat to his homeland.[32]:160–161

Furthermore, an East Roman force had crossed the Danube under the command of another officer also named Aetius—who had participated in the Council of Chalcedon the previous year—and proceeded to defeat the Huns who had been left behind by Attila to safeguard their home territories. Attila, hence, faced heavy human and natural pressures to retire "from Italy without ever setting foot south of the Po".[32]:163 As Hydatiuswrites in his Chronica Minora:

The Huns, who had been plundering Italy and who had also stormed a number of cities, were victims of divine punishment, being visited with heaven-sent disasters: famine and some kind of disease. In addition, they were slaughtered by auxiliaries sent by the Emperor Marcian and led by Aetius, and at the same time, they were crushed in their [home] settlements ... Thus crushed, they made peace with the Romans and all returned to their homes.[34]

Death

The Huns, led by Attila, invade Italy (Attila, the Scourge of God, by Ulpiano Checa, 1887).

Marcian was the successor of Theodosius, and he had ceased paying tribute to the Huns in late 450 while Attila was occupied in the west. Multiple invasions by the Huns and others had left the Balkans with little to plunder.[citation needed] After Attila left Italy and returned to his palace across the Danube, he planned to strike at Constantinople again and reclaim the tribute which Marcian had stopped. However, he died in the early months of 453.

The conventional account from Priscus says that Attila was at a feast celebrating his latest marriage, this time to the beautiful young Ildico (the name suggests Gothic or Ostrogoth origins).[32]:164 In the midst of the revels, however, he suffered a severe nosebleed and choked to death in a stupor. An alternative theory is that he succumbed to internal bleeding after heavy drinking, possibly a condition called esophageal varices, where dilated veins in the lower part of the esophagus rupture leading to death by hemorrhage.[35]

Another account of his death was first recorded 80 years after the events by Roman chronicler Marcellinus Comes. It reports that "Attila, King of the Huns and ravager of the provinces of Europe, was pierced by the hand and blade of his wife".[36] Most scholars reject these accounts as no more than hearsay, preferring instead the account given by Attila's contemporary Priscus. Priscus' version, however, has recently come under renewed scrutiny by Michael A. Babcock.[37]Based on detailed philological analysis, Babcock concludes that the account of natural death given by Priscus was an ecclesiastical "cover story", and that Emperor Marcian (who ruled the Eastern Roman Empire from 450 to 457) was the political force behind Attila's death.[37] Jordanes recounts:

On the following day, when a great part of the morning was spent, the royal attendants suspected some ill and, after a great uproar, broke in the doors. There they found the death of Attila accomplished by an effusion of blood, without any wound, and the girl with downcast face weeping beneath her veil. Then, as is the custom of that race, they plucked out the hair of their heads and made their faces hideous with deep wounds, that the renowned warrior might be mourned, not by effeminate wailings and tears, but by the blood of men. Moreover a wondrous thing took place in connection with Attila's death. For in a dream some god stood at the side of Marcian, Emperor of the East, while he was disquieted about his fierce foe, and showed him the bow of Attila broken in that same night, as if to intimate that the race of Huns owed much to that weapon. This account the historian Priscus says he accepts upon truthful evidence. For so terrible was Attila thought to be to great empires that the gods announced his death to rulers as a special boon.

His body was placed in the midst of a plain and lay in state in a silken tent as a sight for men's admiration. The best horsemen of the entire tribe of the Huns rode around in circles, after the manner of circus games, in the place to which he had been brought and told of his deeds in a funeral dirge in the following manner: "The chief of the Huns, King Attila, born of his sire Mundiuch, lord of bravest tribes, sole possessor of the Scythian and German realms—powers unknown before—captured cities and terrified both empires of the Roman world and, appeased by their prayers, took annual tribute to save the rest from plunder. And when he had accomplished all this by the favor of fortune, he fell, not by wound of the foe, nor by treachery of friends, but in the midst of his nation at peace, happy in his joy and without sense of pain. Who can rate this as death, when none believes it calls for vengeance?"

When they had mourned him with such lamentations, a strava, as they call it, was celebrated over his tomb with great revelling. They gave way in turn to the extremes of feeling and displayed funereal grief alternating with joy. Then in the secrecy of night they buried his body in the earth. They bound his coffins, the first with gold, the second with silver and the third with the strength of iron, showing by such means that these three things suited the mightiest of kings; iron because he subdued the nations, gold and silver because he received the honors of both empires. They also added the arms of foemen won in the fight, trappings of rare worth, sparkling with various gems, and ornaments of all sorts whereby princely state is maintained. And that so great riches might be kept from human curiosity, they slew those appointed to the work—a dreadful pay for their labor; and thus sudden death was the lot of those who buried him as well as of him who was buried.

— Jordanes, in his Getica[6]:254–259

Attila's sons Ellac, Dengizich and Ernak, "in their rash eagerness to rule they all alike destroyed his empire".[6]:259 They "were clamoring that the nations should be divided among them equally and that warlike kings with their peoples should be apportioned to them by lot like a family estate".[6]:259 Against the treatment as "slaves of the basest condition" a Germanic alliance led by the Gepid ruler Ardaric (who was noted for great loyalty to Attila[6]:199) revolted and fought with the Huns in Pannonia in the Battle of Nedao 454 AD.[6]:260–262 Attila's eldest son Ellac was killed in that battle.[6]:262 Attila's sons "regarding the Goths as deserters from their rule, came against them as though they were seeking fugitive slaves", attacked Ostrogothic co-ruler Valamir (who also fought alongside Ardaric and Attila at the Catalaunian Plains[6]:199), but were repelled, and some group of Huns moved to Scythia (probably those of Ernak).[6]:268–269 His brother Dengizich attempted a renewed invasion across the Danube in 468 AD, but was defeated at the Battle of Bassianae by the Ostrogoths.[6]:272–273 Dengizich was killed by Roman-Gothic general Anagast the following year, after which the Hunnic dominion ended.[10]:168

Attila's many children and relatives are known by name and some even by deeds, but soon valid genealogical sources all but dried up, and there seems to be no verifiable way to trace Attila's descendants. This has not stopped many genealogists from attempting to reconstruct a valid line of descent for various medieval rulers. one of the most credible claims has been that of the Nominalia of the Bulgarian khans for mythological Avitohol and Irnik from the Dulo clan of the Bulgars.[38]:103[15]:59, 142[39]

Later folklore and iconography

Attila himself is said to have claimed the titles "Descendant of the Great Nimrod", and "King of the Huns, the Goths, the Danes, and the Medes"—the last two peoples being mentioned to show the extent of his control over subject nations even on the peripheries of his domain.[40]

Jordanes embellished the report of Priscus, reporting that Attila had possessed the "Holy War Sword of the Scythians", which was given to him by Mars and made him a "prince of the entire world".[41][42]

By the end of the 12th century the royal court of Hungary proclaimed their descent from Attila. Lampert of Hersfeld's contemporary chronicles report that shortly before the year 1071, the Sword of Attila had been presented to Otto of Nordheim by the exiled queen of Hungary, Anastasia of Kiev.[43] This sword, a cavalry sabre now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, appears to be the work of Hungarian goldsmiths of the ninth or tenth century.[44]

An anonymous chronicler of the medieval period represented the meeting of Pope Leo and Atilla as attended also by Saint Peter and Saint Paul, "a miraculous tale calculated to meet the taste of the time"[45] This apotheosis was later portrayed artistically by the Renaissance artist Raphael and sculptor Algardi, whom eighteenth-century historian Edward Gibbon praised for establishing one of the noblest legends of ecclesiastical tradition".[46]

According to a version of this narrative related in the Chronicon Pictum, a mediaeval Hungarian chronicle, the Pope promised Attila that if he left Rome in peace, one of his successors would receive a holy crown (which has been understood as referring to the Holy Crown of Hungary).

Some histories and chronicles describe him as a great and noble king, and he plays major roles in three Norse sagas: Atlakviða,[47] Volsunga saga,[48] and Atlamál.[47] The Polish Chronicle represents Attila's name as Aquila.[49]

Frutolf of Michelsberg and Otto of Freising pointed out that some songs as "vulgar fables" made Theoderic the Great, Attila and Ermanaric contemporaries, when any reader of Jordanes knew that this was not the case.[50] This refers to the so-called historical poems about Dietrich von Bern (Theoderic), in which Etzel (Attila) is Dietrich's refuge in exile from his wicked uncle Ermenrich (Ermanaric). Etzel is most prominent in the poems Dietrichs Flucht and Die Rabenschlacht. Etzel also appears as Kriemhild's second noble husband in the Nibelungenlied, in which Kriemhild causes the destruction of both the Hunnish kingdom and that of her Burgundian relatives.

In 1812, Ludwig van Beethoven conceived the idea of writing an opera about Attila and approached August von Kotzebue to write the libretto. It was, however, never written.[51] In 1846, Giuseppe Verdi wrote the opera Attila_(opera), loosely based on episodes in Attila's invasion of Italy.

In World War I, Allied propaganda referred to Germans as the "Huns", based on a 1900 speech by Emperor Wilhelm II praising Attila the Hun's military prowess, according to Jawaharlal Nehru's Glimpses of World History.[52] Der Spiegel commented on November 6, 1948, that the Sword of Attila was hanging menacingly over Austria.[53]

American writer Cecelia Holland wrote The Death of Attila (1973), a historical novel in which Attila appears as a powerful background figure whose life and death deeply impact the protagonists, a young Hunnic warrior and a Germanic one.

The name has many variants in several languages: Atli and Atle in Old Norse; Etzel in Middle High German (Nibelungenlied); Ætla in Old English; Attila, Atilla, and Etele in Hungarian (Attila is the most popular); Attila, Atilla, Atilay, or Atila in Turkish; and Adil and Edil in Kazakh or Adil ("same/similar") or Edil ("to use") in Mongolian.

In modern Hungary and in Turkey, "Attila" and its Turkish variation "Atilla" are commonly used as a male first name. In Hungary, several public places are named after Attila; for instance, in Budapest there are 10 Attila Streets, one of which is an important street behind the Buda Castle. When the Turkish Armed Forces invaded Cyprus in 1974, the operations were named after Attila ("The Attila Plan").[54]

The 1954 Universal International film Sign of the Pagan starred Jack Palance as Attila.

(source : Attila, Wikipedia)

5. 453-454 시기

四十三年秋七月 신라 북쪽 변경을 침략하다 (455)

四十四年 남송에 조공하다 (456)

457-462 : 공백 (6년)

*** Ellac (453-454)

Ellac (died in 454 AD) was the oldest son of Attila (434–453) and Kreka.[1] After Attila's death in 453 AD, his Empire crumbled and its remains were ruled by his three sons, Ellac, Dengizich and Ernak. He ruled shortly, and died at the Battle of Nedao in 454 AD.[2] Ellac was succeeded by brothers Dengizich and Ernak.

History

In 448 or 449 AD, as Priscus recounts "Onegesius along with the eldest of Attila's children, had been sent to the Akateri, a Scythian [Hunnic] people, whom he was bringing into an alliance with Attila".[3] As the Akatziroi tribes and clans were ruled by different leaders, emperor Theodosius II tried with gifts to spread animosity among them, but the gifts were not delivered according to rank, Kouridachos, warned and called Attila against fellow leaders.[4] So Attila did, Kardach stayed with his tribe or clan in own territory, while the rest of the Akatziroi became subjected to Attila.[4] Attila "desired to make his eldest son their king, and so sent Onegesios to do it".[4] Onegesios returned with Ellac, who "had taken a spill and broken his right hand".[5]

Priscus also mentions the number of sons "Onegesios was seated on a chair to the right of the king's couch, and opposite Onegesios two [Dengizich and Ernak] of Attila's children were sitting on a chair. The eldest [Ellac] was seated on Attila's couch, not near him but at the edge, looking at the ground out of respect for his father".[6]

After the rites of Attila's death in 453, according to Jordanes in Getica, the sons Ellac, Dengizich and Ernak (but possibly existed also other sons who pretended the throne[7]):

"...since young minds are usually excited by the chance to snatch power, the heirs of Attila began contesting the kingship. All desiring to rule autonomously, they all destroyed the empire simultaneously. Thus an abundance of heirs often burdens kingdoms more than a lack of them. Attila's sons ... demanded that the subject nations be divided among them by equal lot in order that, as with household property, warlike kings and their people might be distributed by lot".[8]

A coalition of Germanic tribes, led by Ardaric, king of the Gepids, revolted against such slavery treatment, and "so they were armed for mutual destruction. War was waged in Pannonia, next to a river called Nedao. Various nations Attila had held in his sway came into combat there ... Goths, Gepids, Rugii, Suavi, Huns, Alans and Heruli...".[9] By "slavery" status is considered the pay of tributes and military service.[7] There were many "grim clashes", but unexpected victory fell to the Gepids. Ardaric and his allies annihilated nearly 30,000 Huns and their allies.[10] In the battle Attila's oldest son, Ellac, died.[2] According to Priscus:

"[His] father was said to have loved so much beyond his other children that he placed him first among all the various children in the kingdom. His fortune, however, was not in harmony with his father's desire. For it is undisputed that, after slaughtering many enemies, he was killed so heroically that his father, if he had outlived him, would have wished to die so gloriously".[10]

Jordanes recounts:

"When Ellac was slain, his remaining brothers were put to fight near the shore of the Sea of Pontus where we have said the Goths settled. And so yielded the Huns to whom the whole world was once thought to yield: their disintegration was so calamitous that a nation which, with their forces united, used to terrify, when divided, tumbled down ... Many nations, by sending embassies, came to Roman lands and were welcomed by the emperor Marcian ... Now when the Goths saw the Gepids defending for themselves the territory of the Huns, and the people of the Huns dwelling again in their ancient abodes, they preferred to ask for lands from the Roman Empire, rather than invade the lands of others with dangers to themselves. So they received Pannonia".[11][10]

After the battle Attila's largely Germanic subject tribes started to reassert their independence.[12] However, it was not sudden, and not all freed themselves.[13] The Huns "turned in flight and sought the parts of Scythia which border on the stream of the river Danaber, which the Huns call in their own tongue Var".[14] Hernak "chose a home in the most distant part of Scythia Minor".[15] Not all Huns immediately leave the Pannonian Basin, yet only Middle Danube.[16] Some Huns remained in Dacia Ripensis i.e. Lower Danube, Moesia and Thrace.[15]

Etymology

Several scholars derive Ellac from a word akin to Old Turkic älik / ilik / ilig ("prince, ruler, king),[17][18] which derives from *el (realm) + lä-g (to rule, the rule).[19] The name thus appears to be a title rather than a personal name.[17]

(source : Ellac(453-454), Wikipedia)

6-1. 455-469 시기

四十三年秋七月 신라 북쪽 변경을 침략하다 (455)

四十四年 남송에 조공하다 (456)

457-462 : 공백 (6년)

*** Dengizich (454-469, co-ruler with Ernak)

Dengizich (died in 469), was a Hunnic ruler and son of Attila. After Attila's death in 453 AD, his Empire crumbled and its remains were ruled by his three sons, Ellac, Dengizich and Ernak. He succeeded his older brother Ellac in 454 AD, and probably ruled simultaneously over the Huns in dual kingship with his brother Ernak, but separate divisions in separate lands.[1]

History

The oldest brother Ellac died in 454 AD, at the Battle of Nedao.[2] Jordanes recorded "When Ellac was slain, his remaining brothers were put to fight near the shore of the Sea of Pontus where we have said the Goths settled ... dwelling again in their ancient abodes".[3] Jordanes recounts events in c. 454-455: