Odyssey

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigation Jump to search

This article is about Homer's epic poem. For other uses, see Odyssey (disambiguation).

"Homer's Odyssey" redirects here. For The Simpsons episode, see Homer's Odyssey (The Simpsons).

|

| Ancient Greece portal Myths portal |

DeitiesHeroes and heroismRelated

The Odyssey (/ˈɒdəsi/;[1] Greek: Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia; Attic Greek: [o.dýs.sej.ja]) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still read by contemporary audiences.

As with the Iliad, the poem is divided into 24 books. It follows the Greek hero Odysseus, king of Ithaca, and his journey home after winning the Trojan War. It takes Odysseus ten years to reach Ithaca after the ten-year Trojan War. In his absence, Odysseus is assumed dead, and his wife Penelope and son Telemachus must contend with a group of unruly suitors who compete for Penelope's hand in marriage.

The first English translation of the Odyssey was in the 16th century, but the poem was known earlier than 566 BCE, when Peisistratos created a festival which featured performances of the Homeric poems. In antiquity, Homer’s authorship of the Odyssey and Iliad was not questioned, but contemporary scholarship predominately assumes that the poems were composed independently, and the stories themselves formed as part of a long oral tradition. Given widespread illiteracy, the poem was performed by an aoidos or rhapsode, and more likely to be heard than read.

A few noteworthy elements of the text are its non-linear structure and unreliable narrator. Scholars still reflect on the narrative significance of certain groups in the poem, such as women and slaves, who have more influence over the story than they would have had in the historical Ancient Greece. This focus is especially remarkable when considered beside the Iliad, which centres the exploits of soldiers and kings during the Trojan War.

The Odyssey is regarded as one of the most significant works of the Western canon. Adaptations and re-imaginings continue to be produced across a wide variety of mediums. In 2018, when BBC Culture polled experts around the world to find literature's most enduring narrative, the Odyssey topped the list.

Contents

- 1 Synopsis

- 2 Structure

- 3 Odysseus

- 4 Geography of the Odyssey

- 5 Influences on the Odyssey

- 6 Themes and patterns

- 7 Textual history

- 8 Cultural influence

- 9 See also

- 10 References

- 11 Further reading

- 12 External links

Synopsis

Exposition

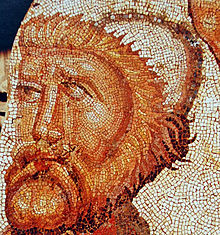

A mosaic depicting Odysseus, from the villa of La Olmeda, Pedrosa de la Vega, Spain, late 4th-5th centuries AD

The Odyssey begins after the end of the ten-year Trojan War (the subject of the Iliad), from which Odysseus, king of Ithaca, has still not returned due to angering Poseidon, the god of the sea. Odysseus' son, Telemachus, is about 20 years old and is sharing his absent father's house on the island of Ithaca with his mother Penelope and "the Suitors," a crowd of 108 boisterous young men who each aim to persuade Penelope for her hand in marriage, all the while reveling in the king's palace and eating up his wealth.

Odysseus' protectress, the goddess Athena, asks Zeus, king of the gods, to finally allow Odysseus to return home when Poseidon is absent from Mount Olympus. Then, disguised as a chieftain named Mentes, Athena visits Telemachus to urge him to search for news of his father. He offers her hospitality and they observe the suitors dining rowdily while Phemius, the bard, performs a narrative poem for them.

That night, Athena, disguised as Telemachus, finds a ship and crew for the true prince. The next morning, Telemachus calls an assembly of citizens of Ithaca to discuss what should be done with the insolent suitors, who then scoff at Telemachus. Accompanied by Athena (now disguised as Mentor), the son of Odysseus departs for the Greek mainland, to the household of Nestor, most venerable of the Greek warriors at Troy, who resided in Pylos after the war.

From there, Telemachus rides to Sparta, accompanied by Nestor's son. There he finds Menelaus and Helen, who are now reconciled. Both Helen and Menelaus also say that they returned to Sparta after a long voyage by way of Egypt. There, on the island of Pharos, Menelaus encounters the old sea-god Proteus, who told him that Odysseus was a captive of the nymph Calypso. Telemachus learns the fate of Menelaus' brother, Agamemnon, king of Mycenae and leader of the Greeks at Troy: he was murdered on his return home by his wife Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus. The story briefly shifts to the suitors, who have only just now realized that Telemachus is gone. Angry, they formulate a plan to ambush his ship and kill him as he sails back home. Penelope overhears their plot and worries for her son's safety.

Escape to the Phaeacians

Charles Gleyre, Odysseus and Nausicaä

In the course of Odysseus' seven years as a captive of the goddess Calypso on an island, she has fallen deeply in love with him, even though he spurns her offers of immortality as her husband and still mourns for home. She is ordered to release him by the messenger god Hermes, who has been sent by Zeus in response to Athena's plea. Odysseus builds a raft and is given clothing, food, and drink by Calypso. When Poseidon learns that Odysseus has escaped, he wrecks the raft but, helped by a veil given by the sea nymph Ino, Odysseus swims ashore on Scherie, the island of the Phaeacians. Naked and exhausted, he hides in a pile of leaves and falls asleep.

The next morning, awakened by girls' laughter, he sees the young Nausicaä, who has gone to the seashore with her maids after Athena told her in a dream to do so. He appeals for help. She encourages him to seek the hospitality of her parents, Arete and Alcinous. Alcinous promises to provide him a ship to return him home, without knowing who Odysseus is.

He remains for several days. Odysseus asks the blind singer Demodocus to tell the story of the Trojan Horse, a stratagem in which Odysseus had played a leading role. Unable to hide his emotion as he relives this episode, Odysseus at last reveals his identity. He then tells the story of his return from Troy.

Odysseus' account of his adventures

Odysseus Overcome by Demodocus' Song, by Francesco Hayez, 1813–15

Odysseus recounts his story to the Phaeacians. After a failed raid, Odysseus and his twelve ships were driven off course by storms. Odysseus visited the lotus-eaters who gave his men their fruit that caused them to forget their homecoming. Odysseus had to drag them back to the ship by force.

Afterwards, Odysseus and his men landed on a lush, uninhabited island near the land of the Cyclopes. The men then landed on shore and entered the cave of Polyphemus, where they found all the cheeses and meat they desired. Upon returning home, Polyphemus sealed the entrance with a massive boulder and proceeded to eat Odysseus' men. Odysseus devised an escape plan in which he, identifying himself as "Nobody," plied Polyphemus with wine and blinded him with a wooden stake. When Polyphemus cried out, his neighbors left after Polyphemus claimed that "Nobody" had attacked him. Odysseus and his men finally escaped the cave by hiding on the underbellies of the sheep as they were let out of the cave.

As they escaped, however, Odysseus, taunting Polyphemus, revealed himself. The Cyclops prays to his father Poseidon, asking him to curse Odysseus to wander for ten years. After the escape, Aeolus gave Odysseus a leather bag containing all the winds, except the west wind, a gift that should have ensured a safe return home. Just as Ithaca came into sight, the sailors opened the bag while Odysseus slept, thinking it contained gold. The winds flew out and the storm drove the ships back the way they had come. Aeolus, recognizing that Odysseus has drawn the ire of the gods, refused to further assist him.

After the cannibalistic Laestrygonians destroyed all of his ships except his own, he sailed on and reached the island of Aeaea, home of witch-goddess Circe. She turned half of his men into swine with drugged cheese and wine. Hermes warned Odysseus about Circe and gave Odysseus an herb called moly, making him resistant to Circe's magic. Odysseus forced Circe to change his men back to their human form, and was seduced by her.

They remained with her for one year. Finally, guided by Circe's instructions, Odysseus and his crew crossed the ocean and reached a harbor at the western edge of the world, where Odysseus sacrificed to the dead. Odysseus summoned the spirit of the prophet Tiresias and was told that he may return home if he is able to stay himself and his crew from eating the sacred livestock of Helios on the island of Thrinacia and that failure to do so would result in the loss of his ship and his entire crew. For Odysseus' encounter with the dead, see Nekuia.

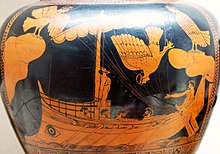

Odysseus and the Sirens, eponymous vase of the Siren Painter, c. 480-470 BC (British Museum)

Returning to Aeaea, they buried Elpenor and were advised by Circe on the remaining stages of the journey. They skirted the land of the Sirens. All of the sailors had their ears plugged up with beeswax, except for Odysseus, who was tied to the mast as he wanted to hear the song. He told his sailors not to untie him as it would only make him drown himself. They then passed between the six-headed monster Scylla and the whirlpool Charybdis. Scylla claims six of his men.

Next, they landed on the island of Thrinacia, with the crew overriding Odysseus's wishes to remain away from the island. Zeus caused a storm which prevented them leaving, causing them to deplete the food given to them by Circe. While Odysseus was away praying, his men ignored the warnings of Tiresias and Circe and hunted the sacred cattle of Helios. The Sun God insisted that Zeus punish the men for this sacrilege. They suffered a shipwreck and all but Odysseus drowned. Odysseus clung to a fig tree. Washed ashore on Ogygia, he remained there as Calypso's lover.

Return to Ithaca

Athena Revealing Ithaca to Ulysses by Giuseppe Bottani (18th century)

Having listened to his story, the Phaeacians agree to provide Odysseus with more treasure than he would have received from the spoils of Troy. They deliver him at night, while he is fast asleep, to a hidden harbour on Ithaca.

Odysseus awakens and believes that he has been dropped on a distant land before Athena appears to him and reveals that he is indeed on Ithaca. She hides his treasure in a nearby cave and disguises him as an elderly beggar so he can see how things stand in his household. He finds his way to the hut of one of his own slaves, swineherd Eumaeus, who treats him hospitably and speaks favorably of Odysseus. After dinner, the disguised Odysseus tells the farm laborers a fictitious tale of himself.

Telemachus sails home from Sparta, evading an ambush set by the Suitors. He disembarks on the coast of Ithaca and meets Odysseus. Odysseus identifies himself to Telemachus (but not to Eumaeus), and they decide that the Suitors must be killed. Telemachus goes home first. Accompanied by Eumaeus, Odysseus returns to his own house, still pretending to be a beggar. He is ridiculed by the Suitors in his own home, especially Antinous. Odysseus meets Penelope and tests her intentions by saying he once met Odysseus in Crete. Closely questioned, he adds that he had recently been in Thesprotia and had learned something there of Odysseus's recent wanderings.

Odysseus's identity is discovered by the housekeeper, Eurycleia, when she recognizes an old scar as she is washing his feet. Eurycleia tries to tell Penelope about the beggar's true identity, but Athena makes sure that Penelope cannot hear her. Odysseus swears Eurycleia to secrecy.

Slaying of the Suitors

Ulysse et Télémaque Massacrent les Prétendants de Pénélope by Thomas Degeorge (1812)

The next day, at Athena's prompting, Penelope maneuvers the Suitors into competing for her hand with an archery competition using Odysseus' bow. The man who can string the bow and shoot an arrow through a dozen axe heads would win. Odysseus takes part in the competition himself: he alone is strong enough to string the bow and shoot the arrow through the dozen axe heads, making him the winner. He then throws off his rags and kills Antinous with his next arrow. Odysseus kills the other Suitors, first using the rest of the arrows and then by swords and spears once both sides armed themselves. Once the battle is won, Telemachus also hangs twelve of their household maids whom Eurycleia identifies as guilty of betraying Penelope or having sex with the Suitors. Odysseus identifies himself to Penelope. She is hesitant but recognizes him when he mentions that he made their bed from an olive tree still rooted to the ground.

Structure

The Odyssey is written in dactylic hexameter.[2] It opens in medias res, in the middle of the overall story, with prior events described through flashbacks and storytelling.[3]

In the Classical period, some of the books (individually and in groups) were commonly given their own titles:

- Book 1–4: Telemachy (Telemachus + mákhē, 'battle')—the story focuses on the perspective of Telemachus.[4]

- Books 9–12: Apologoi—Odysseus recalls his adventures for his Phaeacian hosts.[5]

- Book 22: Mnesterophonia ('slaughter of the suitors'; Mnesteres, 'suitors' + phónos, 'slaughter').[6]

Book 22 concludes the Greek Epic Cycle, though fragments remain of the "alternative ending" of sorts known as the Telegony. The Telegony aside, the last 548 lines of the Odyssey, corresponding to Book 24, are believed by many scholars to have been added by a slightly later poet.[7]

Odysseus

Main article: Odysseus

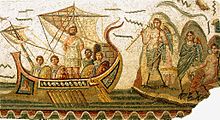

A Roman mosaic depicting a maritime scene with Odysseus (Latin: Ulysses) and the Sirens, from Carthage, 2nd century AD, now in the Bardo Museum, Tunisia

A key attribute of Odysseus (Latin Ulixes, often now Ulysses)[8] in the Odyssey is his outstanding intelligence (Ancient Greek: mêtis).[9] In the Iliad, the characters often serve as foils to one another, but in the Odyssey, Odysseus becomes peerless, and "no living male character in the poem is portrayed as a match for him."[10] To this end, Odysseus is closely associated with two gods: Zeus and Athena.[10]

In the Odyssey, however, Odysseus is more closely identified with Athena. This is one way that the poem ascribes cunning intelligence to Odysseus. An explicit comparison between the pair is made by Athena herself: "[E]ach tries to deceive the other until Athena, laughing, puts a stop to the contest, reminding the hero that 'you of all mortals are the best for plans and speeches, while I among all the gods am famed for wits and wiles'".[11] They are also similar in their use of disguises,[12] utilising them throughout the poem. Athena provides Odysseus with some.[13]

Towards the end of the poem, Odysseus forms "a clever plan to slay the suitors which involves a contest to string [his] mighty bow and shoot an arrow through a line of ax handles. The plan has been carefully formulated to allow Odysseus to catch the suitors off guard and to provide the element of surprise he needs to overpower the suitors against such great odds."[14] Odysseus' cunning enables him to overpower and defeat his opponents, even when they are physically superior to him.[11][14] This mirrors an earlier episode in the poem, where Odysseus defeats the captor Cyclops by disguising himself, then blinding him while unable to defend himself.[15]

Geography of the Odyssey

Main articles: Homer's Ithaca and Geography of the Odyssey

The events in the main sequence of the Odyssey (excluding Odysseus' embedded narrative of his wanderings) take place in the Peloponnese and in what are now called the Ionian Islands.[16] There are difficulties in the apparently simple identification of Ithaca, the homeland of Odysseus, which may or may not be the same island that is now called Ithakē (modern Greek: Ιθάκη).[17] The wanderings of Odysseus as told to the Phaeacians, and the location of the Phaeacians' own island of Scheria, pose more fundamental problems, if geography is to be applied: scholars, both ancient and modern, are divided as to whether or not any of the places visited by Odysseus (after Ismaros and before his return to Ithaca) are real.[18]

Influences on the Odyssey

Terracotta plaque of the Mesopotamian ogre Humbaba, believed to be a possible inspiration for the figure of Polyphemus

Scholars have seen strong influences from Near Eastern mythology and literature in the Odyssey.[19] Martin West notes substantial parallels between the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Odyssey.[20] Both Odysseus and Gilgamesh are known for traveling to the ends of the earth, and on their journeys go to the land of the dead.[21] On his voyage to the underworld, Odysseus follows instructions given to him by Circe, whose is located at the edges of the world and is associated through imagery with the sun.[22] Like Odysseus, Gilgamesh gets directions on how to reach the land of the dead from a divine helper: the goddess Siduri, who, like Circe, dwells by the sea at the ends of the earth, whose home is also associated with the sun. Gilgamesh reaches Siduri's house by passing through a tunnel underneath Mt. Mashu, the high mountain from which the sun comes into the sky.[23] West argues that the similarity of Odysseus' and Gilgamesh's journeys to the edges of the earth are the result of the influence of the Gilgamesh epic upon the Odyssey.[24]

In 1914, paleontologist Othenio Abel surmised the origins of the Cyclops to be the result of ancient Greeks finding an elephant skull.[25] The enormous nasal passage in the middle of the forehead could have looked like the eye socket of a giant, to those who had never seen a living elephant.[25] Classical scholars, on the other hand, have long known that the story of the Cyclops was originally a folk tale, which existed independently of the Odyssey and which became part of it at a later date. Similar stories are found in cultures across Europe and the Middle East.[26]:127–31 According to this explanation, the Cyclops was originally simply a giant or ogre, much like Humbaba in the Epic of Gilgamesh.[26]:127–31 Graham Anderson suggests that the addition about it having only one eye was invented to explain how the creature was so easily blinded.[26]:124–5

Themes and patterns

Homecoming

Odissea (1794)

Homecoming (Ancient Greek: νόστος, nostos) is a central theme of the Odyssey.[27] Anna Bonafazi of the University of Cologne writes that, in Homer, nostos is "return home from Troy, by sea".[28]

Agatha Thornton examines nostos in the context of characters other than Odysseus, in order to provide an alternative for what might happen after the end of the Odyssey.[29] For instance, one example is that of Agamemnon's homecoming versus Odysseus'. Upon Agamemnon's return, his wife Clytemnestra and her lover, Aegisthus kill Agamemnon. Agamemnon's son, Orestes, out of vengeance for his father's death, kills Aegisthus. This parallel compares the death of the suitors to the death of Aegisthus and sets Orestes up as an example for Telemachus.[29] Also, because Odysseus knows about Clytemnestra's betrayal, Odysseus returns home in disguise in order to test the loyalty of his own wife, Penelope.[29] Later, Agamemnon praises Penelope for not killing Odysseus. It is because of Penelope that Odysseus has fame and a successful homecoming. This successful homecoming is unlike Achilles, who has fame but is dead, and Agamemnon, who had an unsuccessful homecoming resulting in his death.[29]

Wandering

Only two of Odysseus's adventures are described by the narrator. The rest of Odysseus' adventures are recounted by Odysseus himself. The two scenes described by the narrator are Odysseus on Calypso's island and Odysseus' encounter with the Phaeacians. These scenes are told by the poet to represent an important transition in Odysseus' journey: being concealed to returning home.[30]

Calypso's name comes from the Greek word kalúptō (καλύπτω), meaning 'to cover' or 'conceal', which is apt, as this is exactly what she does with Odysseus.[31] Calypso keeps Odysseus concealed from the world and unable to return home. After leaving Calypso's island, the poet describes Odysseus' encounters with the Phaeacians—those who "convoy without hurt to all men"[32]—which represents his transition from not returning home to returning home.[30] Also, during Odysseus' journey, he encounters many beings that are close to the gods. These encounters are useful in understanding that Odysseus is in a world beyond man and that influences the fact he cannot return home.[30] These beings that are close to the gods include the Phaeacians who lived near the Cyclopes,[33] whose king, Alcinous, is the great-grandson of the king of the giants, Eurymedon, and the grandson of Poseidon.[30] Some of the other characters that Odysseus encounters are the cyclops Polyphemus, the son of Poseidon; Circe, a sorceress who turns men into animals; and the cannibalistic giants, the Laestrygonians.[30]

Guest-friendship

Throughout the course of the epic, Odysseus encounters several examples of xenia ("guest-friendship"), which provide models of how hosts should and should not act.[34][35] The Phaeacians demonstrate exemplary guest-friendship by feeding Odysseus, giving him a place to sleep, and granting him many gifts and a safe voyage home, which are all things a good host should do. Polyphemus demonstrates poor guest-friendship. His only "gift" to Odysseus is that he will eat him last.[35] Calypso also exemplifies poor guest-friendship because she does not allow Odysseus to leave her island.[35] Another important factor to guest-friendship is that kingship implies generosity. It is assumed that a king has the means to be a generous host and is more generous with his own property.[35] This is best seen when Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, begs Antinous, one of the suitors, for food and Antinous denies his request. Odysseus essentially says that while Antinous may look like a king, he is far from a king since he is not generous.[36]

According to J. B. Hainsworth, guest-friendship follows a very specific pattern:[37]

- The arrival and the reception of the guest.

- Bathing or providing fresh clothes to the guest.

- Providing food and drink to the guest.

- Questions may be asked of the guest and entertainment should be provided by the host.

- The guest should be given a place to sleep, and both the guest and host retire for the night.

- The guest and host exchange gifts, the guest is granted a safe journey home, and the guest departs.

Another important factor of guest-friendship is not keeping the guest longer than they wish and also promising their safety while they are a guest within the host's home.[34][38]

Testing

Penelope questions Odysseus to prove his identity.

Another theme throughout the Odyssey is testing.[39] This occurs in two distinct ways. Odysseus tests the loyalty of others and others test Odysseus' identity. An example of Odysseus testing the loyalties of others is when he returns home.[39] Instead of immediately revealing his identity, he arrives disguised as a beggar and then proceeds to determine who in his house has remained loyal to him and who has helped the suitors. After Odysseus reveals his true identity, the characters test Odysseus' identity to see if he really is who he says he is.[39] For instance, Penelope tests Odysseus' identity by saying that she will move the bed into the other room for him. This is a difficult task since it is made out of a living tree that would require being cut down, a fact that only the real Odysseus would know, thus proving his identity. For more information on the progression of testing type scenes, read more below.[39]

Testing also has a very specific type scene that accompanies it as well. Throughout the epic, the testing of others follows a typical pattern. This pattern is:[39][38]

- Odysseus is hesitant to question the loyalties of others.

- Odysseus tests the loyalties of others by questioning them.

- The characters reply to Odysseus' questions.

- Odysseus proceeds to reveal his identity.

- The characters test Odysseus' identity.

- There is a rise of emotions associated with Odysseus' recognition, usually lament or joy.

- Finally, the reconciled characters work together.

Omens

Odysseus and Eurycleia by Christian Gottlob Heyne

Omens occur frequently throughout the Odyssey. Within the epic poem, they frequently involve birds.[40] According to Thornton, most crucial is who receives each omen and in what way it manifests. For instance, bird omens are shown to Telemachus, Penelope, Odysseus, and the suitors.[40] Telemachus and Penelope receive their omens as well in the form of words, sneezes, and dreams.[40] However, Odysseus is the only character who receives thunder or lightning as an omen.[41][42] She highlights this as crucial because lightning, as a symbol of Zeus, represents the kingship of Odysseus.[40] Odysseus is associated with Zeus throughout both the Iliad and the Odyssey.[43]

Omens are another example of a type scene in the Odyssey. Two important parts of an omen type scene are the recognition of the omen, followed by its interpretation.[40] In the Odyssey, all of the bird omens — with the exception of the first — show large birds attacking smaller birds.[40][38] Accompanying each omen is a wish which can be either explicitly stated or only implied.[40] For example, Telemachus wishes for vengeance[44] and for Odysseus to be home,[45] Penelope wishes for Odysseus' return,[46] and the suitors wish for the death of Telemachus.[47]

Textual history

Date of composition

The date of the poem is a matter of serious disagreement among classicists. In the middle of the 8th century BCE, the inhabitants of Greece began to adopt a modified version of the Phoenician alphabet to write down their own language.[48] The Homeric poems may have been one of the earliest products of that literacy, and if so, would have been composed some time in the late 8th century.[49] Inscribed on a clay cup found in Ischia, Italy, are the words "Nestor's cup, good to drink from."[50] Some scholars, such as Calvert Watkins, have tied this cup to a description King Nestor's golden cup in the Iliad.[51] If the cup is an allusion to the Iliad, that poem's composition can be dated to 700–750 BCE.[48]

Dating is similarly complicated by the fact that the Homeric poems, or sections of them, were performed regularly by rhapsodes for several hundred years.[48] But the Odyssey as it exists today was likely not significant different from the version which exists today.[49] Aside from minor differences, the Homeric poems gained a canonical place in the institutions of ancient Athens by the 6th century.[52] In 566 BCE, Peisistratos instituted a civic and religious festival called the Panathenaia, which featured performances of Homeric poems.[52]

Archaeological findings

Since the late 19th century many papyri containing parts or even entire chapters have been found in Egypt, with content different from later medieval versions.[53] In 2018, the Greek Cultural Ministry revealed the discovery of a clay tablet near the Temple of Zeus, containing 13 verses from the Odyssey's 14th Rhapsody to Eumaeus. While it was initially reported to date from the 3rd century AD, the date still needs to be confirmed.[54][55]

English translations

See also: English translations of Homer

Emily Wilson, professor of classical studies, at the University of Pennsylvania, noted that, as recently as a decade ago, almost all of the most prominent translators of Greek and Roman literature have been men.[56] She called her experience of translating Homer one of "intimate alienation."[57] Wilson writes in the introduction to her own translation that this has affected the popular conception of characters and events of the Odyssey,[58] Wilson writes that translators, historical and contemporary, have inflected the story with connotations not present in the original text: "For instance, in the scene where Telemachus oversees the hanging of the slaves who have been sleeping with the suitors, most translations introduce derogatory language ("sluts" or "whores") [...] The original Greek does not label these slaves with derogatory language."[58] In the original Greek, the word used is hai, the feminine article, equivalent to "those female people".[59]

Cultural influence

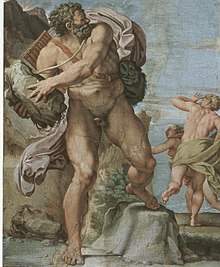

The Cyclops Polyphemus by Annibale Carracci (between 1595 and 1605), showing a scene shared between the Odyssey and Euripides's Cyclops (1922)

Front cover of James Joyce's Ulysses

The Odyssey is regarded as one of the most important foundational works of western literature.[60] It is widely regarded by western literary critics as a timeless classic,[61] and remains one of the oldest works of extant literature commonly read by Western audiences.[62] Historical and contemporary artists alike have creatively re-interpreted the poem for different mediums and audiences.

Literature

- Euripides' Cyclops, the only fully extant satyr play,[63] retells the episode involving Polyphemus with a humorous twist.[64]

- Merugud Uilix maicc Leirtis ('On the Wandering of Ulysses, son of Laertes') is an eccentric Old Irish version of the material, which exists in a 12th-century AD manuscript that linguists believe is based on an 8th-century original.[65]

- Ezra Pound's The Cantos (1917) has a retelling of Odysseus' journey to the underworld as its first canto.[66]

- The poem "Ulysses" by Alfred, Lord Tennyson is narrated by an aged Ulysses who is determined to continue to live life to the fullest.

- James Joyce's modernist novel Ulysses (1922) is a retelling of the Odyssey set in modern-day Dublin. Each chapter in the book has an assigned theme, technique, and correspondences between its characters and those of Homer's Odyssey.[67]

- Derek Walcott's Omeros (1991) is an epic poem which very loosely mirrors the Odyssey, and is set on the Caribbean island of Saint Lucia.

- Daniel Wallace's Big Fish: A Novel of Mythic Proportions (1998) adapts the epic to the American South, while incorporating tall tales into its first-person narrative, as some critics suggest Odysseus does in the Apologoi (Books 9-12).[citation needed]

- Margaret Atwood's The Penelopiad (2005) is a novella retelling the Odyssey from Penelope's perspective.[68]

- Zachary Mason's The Lost Books of the Odyssey (2007) is a series of short stories that rework Homer's original plot in a contemporary style reminiscent of Italo Calvino.

- Madeline Miller's Circe (2018) partially retells Odysseus' time with Circe on Aeaea. The novel includes a novelisation of portions of Books 9 through 12 of Odyssey, but also draws from other aspects of Greek mythology. The novel re-examines Odysseus' character and his relationship with Circe.[69]

Perhaps given the absence of the Telegony, writers have tried to imagine what might come after the Odyssey. In canto XXVI of the Inferno, Dante Alighieri meets Odysseus in the eighth circle of hell, where Odysseus himself appends a new ending to the Odyssey in which he never returns to Ithaca and instead continues his restless adventuring.[70][71] Alfred, Lord Tennysonexpands on this in his 1842 poem "Ulysses".[citation needed] Nikos Kazantzakis continued the story beyond its ending in his epic poem The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel, first published in 1938 in modern Greek.[72]

Film and television adaptations

- Ulysses (1954) is film adaptation starring Kirk Douglas as Ulysses, Silvana Mangano as Penelope and Circe, and Anthony Quinn as Antinous.[73]

- L'Odissea (1968) is a Italian-French-German-Yugoslavian television miniseries praised for its faithful rendering of the original epic.[74]

- Ulysses 31 (1981) is a Japanese-French anime that updates the ancient setting into a 31st-century space opera.

- Ulysses' Gaze (1995), directed by Theo Angelopoulos, has many of the elements of the Odyssey set against the backdrop of the most recent and previous Balkan Wars.[67]

- The Odyssey (1997) is a television miniseries directed by Andrei Konchalovsky and starring Armand Assante as Odysseus and Greta Scacchi as Penelope.[75]

- O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) is a crime comedy-drama film written, produced, co-edited and directed by the Coen Brothers, and is very loosely based on Homer's poem.[76]

Opera and music

- Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria, first performed in 1640, is an opera by Claudio Monteverdi based on the second half of Homer's Odyssey.[77]

- Max Bruch’s choral work Odysseus told the main highlights of the hero’s story.[citation needed]

- Rolf Riehm composed an opera based on the myth, Sirenen – Bilder des Begehrens und des Vernichtens (Sirens – Images of Desire and Destruction) which premiered at the Oper Frankfurt in 2014.[78]

- Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds use the Odyssey to form the "narrative" of the song "More News from Nowhere," released in 2008 as a single and on the album Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!!. In the song, Cave uses a variety of contemporary names to represent the gods and nymphs who populate the Odyssey, and sketches key episodes from the epic across an eight-minute track.[citation needed]

- John Mackey's symphony for concert band, Wine-Dark Sea, tells three of the main highlights of the story in the piece's three movements.[citation needed]

- Robert W. Smith's second symphony for concert band, The Odyssey, tells four of the main highlights of the story in the piece's four movements: The Iliad, The Winds of Poseidon, The Isle of Calypso, and Ithaca.[citation needed]

- Sarah Kirkland Snider's song cycle, Penelope, is based on the faithful wife from Homer's Odyssey.[citation needed]

See also

- Aeneid

- Gulliver's Travels

- English translations of Homer

- List of literary cycles

- Odyssean gods

- Parallels between Virgil's Aeneid and Homer's Iliad and Odyssey

- Sinbad the Sailor

- Sunpadh

- The Voyage of Bran

References

'Thracians' 카테고리의 다른 글

| <펌> Diocese of Thrace (0) | 2021.01.07 |

|---|---|

| <펌> Thrace (0) | 2021.01.07 |

| <펌>Thracian religion (0) | 2020.09.12 |

| <펌> Odrysian Kingdom (480 BC - 46 AD) (0) | 2020.09.07 |

| <펌> Thracians (0) | 2019.02.04 |