Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley

| Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Conquests of Achaemenid Empire | |||||||

Eastern border of the Achaemenid Empire and the kingdoms and cities of ancient India (circa 500 BCE).[1][2][3][4] |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Achaemenid Empire | Mahajanapadas | ||||||

The Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley refers to the Achaemenid military conquest and occupation for about two centuries of territories of the North-western regions of the Indian subcontinent. The conquest of the areas as far as the Indus river is often dated to the time of Cyrus the Great, in the period between 550-539 BCE.[1] The first secure epigraphic evidence, given by the Behistun Inscription inscription, gives a date before or about 518 BCE. Achaemenid penetration into the area of the Indian subcontinent occurred in stages, starting from northern parts of the River Indus and moving southward.[6] These areas of the Indus valley became formal Achaemenid satrapies as mentioned in several Achaemenid inscriptions. The Achaemenid occupation of the Indus Valley ended with the Indian campaign of Alexander the Great circa 323 BCE.[1] The Achaemenid occupation, although less successful than that of the later Greeks, Sakas or Kushans, had the effect of acquainting India to the outer world.[7]

Contents

Background and invasion

The Achaemenid Empire underwent a considerable expansion, both east and west, during the reign of Cyrus the Great (c.600–530 BC), leading the dynasty to take an interest into the region of northwestern India.[1]

- Cyrus the Great

The conquest is often thought to have started circa 535 BCE, during the time of Cyrus the Great (600-530 BCE).[8][9][1] Cyrus probably went as far as the banks of the Indus river and organized the conquered territories under the Satrapy of Gandara (Old Persian cuneiform: ????, Gadāra, also transliterated as Gandāra since the nasal "n" before consonants was omitted in the Old Persian script, and simplified as Gandara)[10] according to the Behistun Inscription.[11] The Province was also referred to as Paruparaesanna(Greek: Parapamisadae) in the Babylonian and Elamite versions of the Behistun inscription.[11] The geographical extent of this province was wider than the Indian Gandhara.[12]Various accounts, such as those of Xenophon or Ctesias, who wrote Indica, also suggest that Cyrus conquered parts of India.[13][1] Another Indian Province was conquered named Sattagydia (?????, Thataguš) in the Behistun inscription. It was probably contiguous to Gandhara, but its actual location is uncertain. Fleming locates it between Arachosiaand the middle Indus.[14] Fleming also mentions Maka, in the area of Gedrosia, as one of the Indian satrapies.[15]

- Darius I

A successor of Cyrus the Great, Darius I was back in 518 BCE. The date of 518 BCE is given by the Behistun inscription, and is also often the one given for the secure occupation of Gandhara in Punjab.[16] Darius I later conquered an additional province that he calls "Hidūš" in his inscriptions (Old Persian cuneiform: ?????, H-i-du-u-š, also transliterated as Hindūš since the nasal "n" before consonants was omitted in the Old Persian script, and simplified as Hindush), corresponding to the Indus Valley.[17][10][18] The Hamadan Gold and Silver Tablet inscription[19] of Darius I also refers to his conquests in India.[1]

The exact area of the Province of Hindush is uncertain. Some scholars have described it as the middle and lower Indus Valley and the approximate region of modern Sindh,[20] but there is no known evidence of Achaemenid presence in this region, and deposits of gold, which Herodotus says was produced in vast quantities by this Province, are also unknown in the Indus delta region.[21] Alternatively, Hindush may have been the region of Taxila and Western Punjab, where there are indications that a Persian satrapy may have existed.[21] There are few remains of Achaemenid presence in the east, but, according to Fleming, the archaeological site of Bhir Mound in Taxila remains the "most plausible candidate for the capital of Achaemenid India", based on the fact that numerous pottery styles similar to those of the Achaemenids in the East have been found there, and that "there are no other sites in the region with Bhir Mound's potential".[22]

According to Herodotus, Darius I sent the Greek explorer Scylax of Caryanda to sail down the Indus river, heading a team of spies, in order to explore the course of the Indus river. After a periplus of 30 months, Scylax is said to have returned to Egypt near the Red Sea, and the seas between the Near East and India were made use of by Darius.[23][24]

Also according to Herodotus, the territories of Gandhara, Sattagydia, Dadicae and Aparytae formed the 7th province of the Achaemenid Empire for tax-payment purposes, while Indus (called Ἰνδός, "Indos" in Greek sources) formed the 20th tax region.

- Achaemenid army

The Achaemenid army was not uniquely Persian. Rather it was composed of many different ethnicities that were part of the vast Achaemenid Empire. The army included Bactrians, Sakas (Scythians), Parthians, Sogdians.[25] Herodotus gives a full list of the ethnicities of the Achaemenid army, in which are included Ionians (Greeks), and even Ethiopians.[26][25] These ethnicities are likely to have been included in the Achaemenid army which invaded India.[25]

The Persians may have later participated, together with Sakas and Greeks, in the campaigns of Chandragupta Maurya to gain the throne of Magadha circa 320 BCE. The Mudrarakshasa states that after Alexander's death, an alliance of "Shaka-Yavana-Kamboja-Parasika-Bahlika" was used by Chandragupta Maurya in his campaign to take the throne in Magadha and found the Mauryan Empire.[27][28][29] The Sakas were the Scythians, the Yavanas were the Greeks, and the Parasikas were the Persians.[28][30] David Brainard Spooner observed of Chandragupta Maurya that "it was with largely the Persian army that he won the throne of India."[29][27]

Inscriptions and accounts

These events were recorded in the imperial inscriptions of the Achaemenids (the Behistun inscription and the Naqsh-i-Rustam inscription, as well as the accounts of Herodotus(483–431 BCE), and of the Hellenistic accounts of the Greek conquests in India (circa 320 BCE). The Greek Scylax of Caryanda, who had been appointed by Darius I to explore the Indian Ocean from the mouth of the Indus to Suez left an account, the Periplous, of which fragments from secondary sources have survived. Hecataeus of Miletus (circa 500 BCE) also wrote about the "Indus Satrapies" of the Achaemenids.

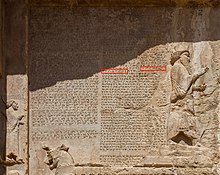

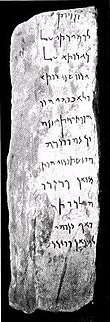

Behistun inscription

The 'DB' Behistun inscription[32] of Darius I (circa 510 BCE) mentions Gandara (????, Gadāra) and the adjacent territory of Sattagydia (?????, Thataguš) as part of the Achaemenid Empire:

From the dating of the Behistun inscription, it is possible to infer that the Achaemenids first conquered the areas of Gandara and Sattagydia circa 518 BCE.

Statue of Darius inscriptions

Hinduš is also mentioned as one of 24 subject countries of the Achaemenid Empire, illustrated with the drawing of a kneeling subject and a hieroglyphic cartridge reading ????? (H-n-d-wꜣ-y), on the Egyptian Statue of Darius I, now in the National Museum of Iran. Sattagydia also appears (?????, S-d-g-wꜣ-ḏꜣ, Sattagydia), and probably Gandara (?????, H-rw-h-d-y, although this could be Arachosia), with their own illustrations.[35][31]

Apadana Palace foundation tablets

Four identical foundation tablets of gold and silver, found in two deposition boxes in the foundations of the Apadana Palace, also contained an inscription by Darius I in Old Persian cuneiform, which describes the extent of his Empire in broad geographical terms, from the Indus valley in the east to Lydia in the west, and from the Scythians beyond Sogdia in the north, to the African Kingdom of Kush in the south. This is known as the DPh inscription.[37][38] The deposition of these foundation tablets and the Apadana coin hoard found under them, is dated to circa 515 BCE.[37]

Naqsh-e Rustam inscription

The DSe inscription[41] and DSm inscription[42] of Darius in Susa gives Thataguš (Sattagydia), Gadāra (Gandara) and Hiduš (Sind) among the nations that he rules.[41][31]

Hidūš (????? in Old Persian cuneiform) also appears later as a Satrapy in the Naqsh-i-Rustam inscription at the end of the reign of Darius, who died in 486 BCE.[31] The DNa inscription[18] on Darius' tomb at Naqsh-i-Rustam near Persepolis records Gadāra (Gandāra) along with Hiduš and Thataguš (Sattagydia) in the list of satrapies.[43]

Achaemenid administration

The nature of the administration under the Achaemenids is uncertain. Even though the Indian provinces are called "satrapies" by convention, there is no evidence of there being any satraps in these provinces. When Alexander invaded the region, he did not encounter Achaemenid satraps in the Indian provinces, but local Indian rulers referred to as hyparchs ("Vice-Regents"), a term that connotes subordination to the Achaemenid rulers.[49] The local rulers may have reported to the satraps of Bactria and Arachosia.[49]

- Achaemenid lists of Provinces

Darius I listed three Indian provinces: Thataguš (Sattagydia), Gandâra (Gandhara) and Hidūš (Sind),[31] in which "Sind" should be understood as "Indus Valley".[50] The three regions remained represented among Achaemenid Provinces on all the tombs of the Achaemenid rulers after Darius, except for the last ruler Darius III who was vanquished by Alexander at Gaugamela, suggesting that the Indians were under Achaemenid dominion at least until 338 BCE, date of the end of the reign of Artaxerxes III, before the accession of Darius III, that is, less than 10 years before the campaigns of Alexander in the East and his victory at Gaugamela.[49] The last known appearance of Gandhara in name as an Achaemenid province is on the list of the tomb of Artaxerxes II, circa 358 BCE, date of his burial.[46][47][48]

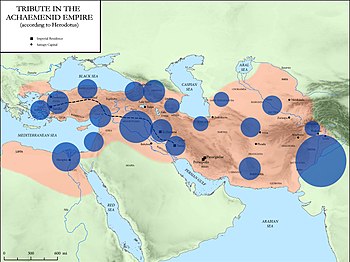

- List of Herodotus

Herodotus (III-91 and III-94), gives a list with a slightly different structure, as some province which are presented separately in the Achaemenid inscriptions are grouped together by Herodotus when he described the tribute paid by each territory.[51][52][53] Herodotus presents Indos (Ἰνδός) as "the 20th province", while "the Sattagydae, Gandarii, Dadicae, and Aparytae" together form "the 7th Province".[53] According to historian A. T. Olmstead, the fact that some Achaemenid regions are grouped together in this list may have represented some loss of territory.[54]

The Hindūš province, remained loyal till Alexander's invasion.[55] Circa 400 BC, Ctesias of Cnidus related that the Persian king was receiving numerous gifts from the kings of "India" (Hindūš).[31][a] Ctesias also reported Indian elephants and Indian mahouts making demonstrations of the elephant's strength at the Achaemenid court.[57]

By about 380 BC, the Persian hold on the region was weakening, but the area continued to be a part of the Achaemenid Empire until Alexander's invasion.[58]

Darius III (c. 380 – July 330 BC) still had Indian units in his army.[31] In particular he had 15 war elephants at the Battle of Gaugamela for his fight against Alexander the Great.[59]

Indian tributes

Apadana Palace

The reliefs at the Apadana Palace in Persepolis describe tribute bearers from 23 satrapies visiting the Achaemenid court. These are located at the southern end of the Apadana Staircase. Among the foreigners the Arabs, the Thracians, the Bactrians, the Indians (from the Indus valley area), the Parthians, the Cappadocians, the Elamites or the Medians. The Indians from the Indus valley are bare-chested, except for their leader, and barefooted and wear the dhoti. They bring baskets with vases inside, carry axes, and drive along a donkey.[61]One man in the Indian procession carries a small but visibly heavy load of four jars on a yoke, suggesting that he was carrying some of the gold dust paid by the Indians as tribute to the Achaemenid court.[60]

According to the Naqsh-e Rustam inscription of Darius I (circa 490 BCE), there were three Achaemenid Satrapies in the subcontinent: Sattagydia, Gandara, Hidūš.[44][62]

Tribute payments

The conquered area was the most fertile and populous region of the Achaemenid Empire. An amount of tribute was fixed according to the richness of each territory.[65][63] India was already fabled for its gold.

Herodotus (who makes several comments on India) published a list of tribute-paying nations, classifying them in 20 Provinces.[66][53] The Province of Indos (Ἰνδός, the Indus valley) formed the 20th Province, and was the richest and most populous of the Achaemenid Provinces.

According to Herodotus, the "Indians" ('Ινδοι, Indoi[67]), as separate from the Gandarei and the Sattagydians, formed the 20th taxation Province, and were required to supply gold dust in tribute to the Achaemenid central government for an amount of 360 Euboean talents (equivalent to about 8300 kg or 8.3 tons of gold annually, a volume of gold that would fit in a cube of side 75 cm).[65][63] The exchange rate between gold and silver at the time of Herodotus being 13 to 1, this was equal in value to the very large amount of 4680 Euboean talents of silver, equivalent to 3600 Babylonian talents of silver (equivalent in value to about 108 tons of silver annually).[65][63] The country of the "Indians" ('Ινδοι, Indoi) was the Achaemenid district paying the largest tribute, and alone represented 32% of the total tribute revenues of the whole Achaemenid Empire.[65][63][31] It also means that Indos was the richest Achaemenid region in the subcontinent, much richer than Gandara or Sattagydia.[31] However the amount of gold in question is quite enormous, so there is a possibility that Herodotus was mistaken and that his own sources actually only meant something like the gold equivalent of 360 Babylonian talents of silver.[21]

The territories of Gandara, Sattagydia, Dadicae (north-west of the Kashmir valley) and the Aparytae (Afridis) are named separately, and were aggregated together for taxation purposes, forming the 7th Achaemenid Province, and paying overall a much lower tribute of 170 talents together (about 5151 kg, or 5.1 tons of silver), hence only about 1.5% of the total revenues of the Achaemenid Empire:[65][63]

The Indians also supplied Yaka wood (teak) for the construction of Achaemenid palaces,[71][62] as well as war elephants such as those used at Gaugamela.[62] The Susa inscriptions of Darius explain that Indian ivory and teak were sold on Persian markets, and used in the construction of his palace.[1]

Contribution to Achaemenid war efforts

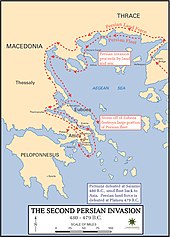

- Second Persian invasion of Greece (480-479 BCE)

Indians were employed in the Achaemenid army of Xerxes in the Second Persian invasion of Greece (480-479 BCE). All troops were stationned in Sardis, Lydia, during the winter of 481-480 BCE to prepare for the invasion.[72][73] In the spring of 480 BCE "Indian troops marched with Xerxes's army across the Hellespont".[15][74] It was the "first-ever force from India to fight on the continent of Europe", storming Greek troops at the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE, and fighting as one of the main nations until the final Battle of Platea in 479 BCE.[75][76][77]

Herodotus, in his description of the multi-ethnic Achaemenid army invading Greece, described the equipment of the Indians:[74]

Herodotus also explains that the Indian cavalry under the Achaemenids had an equipment similar that of their foot soldiers:

The Gandharis had a different equipment, akin to that of the Bactrians:

- Destruction of Athens and Battle of Plataea (479 BCE)

After the first part of the campaign directly under the orders Xerxes I, the Indian troops are reported to have stayed in Greece as one of the 5 main nations among the 300,000 elite troops of General Mardonius. They fought in the last stages of the war, took part in the Destruction of Athens, but were finally vanquished at the Battle of Platea:[81]

At the final Battle of Platea in 479 BCE, Indians formed one of the main corps of Achaemenid troops (one of "the greatest of the nations").[76][77][75][83] They were one of the main battle corps, positioned near the center of the Achaemenid battle line, between the Bactrians and the Sakae, facing against the enemy Greek troops of "Hermione and Eretria and Styra and Chalcis".[84][76] According to modern estimates, the Bactrians, Indians and Sakae probably numbered about 20,000 men altogether, whereas the Persian troops on their left amounted to about 40,000.[85] There were also Greek allies of the Persians, positionned on the right, whom Herodotus numbers at 50,000, a number which however might be "extravagant",[85] and is nowadays estimated to around 20,000.[86] Indians also supplied part of the cavalry, the total of which was about 5,000.[87][86]

- Depictions

Indian soldiers of the three territories of Gandara, Sattagydia (Tathagatus) and Hindush are shown, together with soldiers of all the other nations, supporting the throne of their Achaemenid ruler, at Naqsh-e Rostam on the tombs of Darius I, Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I and Darius II, and at Persepolis on the tombs of Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III. The last Achaemenid ruler Darius III never had time to finish his own tomb due to his hasty defeat by Alexander the Great, and therefore does not have such depictions.[49][70] The soldiers from India are characterized by their particular clothing, only composed of a loin cloth and sandals, with bare upper body, in contrast to all the other ethnicities of the Achaemenid army, who are fully clothed, and in contrast also to the neighbouring provinces of Bactria or Arachosia, who are also fully clothed.[49]

The presence of the three ethnicities of Indian soldiers on the all the tombs of the Achaemenid rulers after Darius, except for the last ruler Darius III who was vanquished by Alexander at Gaugamela, suggest that the Indians were under Achaemenid dominion at least until 338 BCE, date of the end of the reign of Artaxerxes III, before the accession of Darius III, that is, less than 10 years before the campaigns of Alexander in the East and his victory at Gaugamela.[49]

- Indians at the Battle of Gaugamela (331 BCE)

According to Arrian, Indian troops were still deployed under Darius III at the Battle of Gaugamela (331 BCE). He explains that Darius III "obtained the help of those Indians who bordered on the Bactrians, together with the Bactrians and Sogdianians themselves, all under the command of Bessus, the Satrap of Bactria".[49] The Indians in questions were probably from the area of Gandara.[49] Indian "hill-men" are also said by Arrian to have joined the Arachotians under Satrap Barsentes, and are thought to have been either the Sattagydians or the Hindush.[49]

Fifteen Indian war elephants were also part of the army of Darius III at Gaugamela.[59] They had specifically been brought from India.[89] Still, it seems they did not participate to the final battle, probably because of fatigue.[59] This was a relief for the armies of Alexander, who had no previous experience of combat against war elephants.[90] The elephants were captured with the baggage train by the Greeks after the engagement.[91]

Greek and Achaemenid coinage

Coin finds in the Chaman Hazouri hoard in Kabul, or the Shaikhan Dehri hoard in Pushkalavati in Gandhara, near Charsadda, as well as in the Bhir Mound hoard in Taxila, have revealed numerous Achaemenid coins as well as many Greek coins from the 5th and 4th centuries BCE which circulated in the area, at least as far as the Indus during the reign of the Achaemenids, who were in control of the areas as far as Gandhara.[97][98][94][99]

Kabul and Bhir Mound hoards

The Kabul hoard, also called the Chaman Hazouri, Chaman Hazouri or Tchamani-i Hazouri hoard,[97] is a coin hoard discovered in the vicinity of Kabul, Afghanistan. The hoard, discovered in 1933, contained numerous Achaemenid coins as well as many Greek coins from the 5th and 4th centuries BCE.[94] Approximately one thousand coins were in the hoard.[97][98] The hoard is dated to approximately 380 BCE as no coins in the hoard were later than that date.[100]

This numismatic discovery has been very important in studying and dating the history of coinage of India, since it is one of the very rare instances when punch-marked coins can actually be dated, due to their association with known and dated Greek and Achaemenid coins in the hoard.[101] The hoard supports the view that punch-marked coins existed in 360 BCE, as suggested by literary evidence.[101]

Daniel Schlumberger also considers that punch-marked bars, similar to the many punch-marked bars found in north-western India, initially originated in the Achaemenid Empire, rather than in the Indian heartland:

Modern numismatists now tend to consider the Achaemenid punch-marked coins as the precursors of the Indian punch-marked coins.[102][103]

Pushkalavati hoard

In 2007, a small coin hoard was discovered at the site of ancient Pushkalavati (the Shaikhan Dehri hoard) near Charsada in Pakistan. The hoard contained a tetradrachm minted in Athens circa 500/490-485/0 BCE, together with a number of local types as well as silver cast ingots. The hoard contained a tetradrachm minted in Athens circa 500/490-485/0 BCE, typically used as a currency for trade in the Achaemenid Empire, together with a number of local types as well as silver cast ingots. The Athens coin is the earliest known example of its type to be found so far to the east.[104][105]

According to Joe Cribb, these early Greek coins were at the origin of Indian punch-marked coins, the earliest coins developed in India, which used minting technology derived from Greek coinage.[94]

Influence of Achaemenid culture in the Indian subcontinent

Cultural exchanges: Taxila

Taxila (site of Bhir Mound), the "most plausible candidate for the capital of Achaemenid India",[15] was at the crossroad of the main trade roads of Asia, was probably populated by Persians, Greeks and other people from throughout the Achaemenid Empire.[106][107][108] The renowned University of Taxila became the greatest learning centre in the region, and allowed for exchanges between people from various cultures.[109]

- Followers of the Buddha

Several contemporaries, and close followers, of the Buddha are said to have studied in Achaemenid Taxila: King Pasenadi of Kosala, a close friend of the Buddha, Bandhula, the commander of Pasedani's army, Aṅgulimāla, a close follower of the Buddha, and Jivaka, court doctor at Rajagriha and personal doctor of the Buddha.[110] According to Stephen Batchelor, the Buddha may have been influenced by the experiences and knowledge acquired by some of his closest followers in Taxila.[111]

- Pāṇini

The 5th century BCE grammarian Pāṇini lived in an Achaemenid environment.[112][113][114] He is said to have been born in the north-west, in Shalatula near Attock, not far from Taxila, in what was then a satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire following the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley, which technically made him a Persian subject.[112][113][114]

- Kautilya and Chandragupta Maurya

Kautilya, the influential Prime Minister of Chandragupta Maurya, is also said to have been a professor teaching in Taxila.[115] According to Buddhist legend, Kautilya brought Chandragupta Maurya, the future founder of the Mauryan Empire to Taxila as a child, and had him educated there in "all the sciences and arts" of the period, including military sciences, for a period of 7 to 8 years.[116] These legends match Plutarch's assertion that Alexander the Great met with the young Chandragupta while campaigning in the Punjab.[116][117]

Astronomical and astrological knowledge was also probably transmitted to India from Babylon during the 5th century BCE as a consequence of the Achaemenid presence in the sub-continent.[118][119]

Palatial art and architecture: Pataliputra

Various Indian artefacts tend to suggest some Perso-Hellenistic artistic influence in India, mainly felt during the time of the Mauryan Empire.[1] The sculpture of the Masarh lion, found near the Maurya capital of Pataliputra, raises the question of the Achaemenid and Greek influence on the art of the Maurya Empire, and on the western origins of stone carving in India. The lion is carved in Chunar sandstone, like the Pillars of Ashoka, and its finish is polished, a feature of the Maurya sculpture.[120] According to S.P. Gupta, the sculptural style is unquestionably Achaemenid.[120] This is particularly the case for the well-ordered tubular representation of whiskers (vibrissas) and the geometrical representation of inflated veins flush with the entire face.[120] The mane, on the other hand, with tufts of hair represented in wavelets, is rather naturalistic.[120] Very similar examples are however known in Greece and Persepolis.[120] It is possible that this sculpture was made by an Achaemenid or Greek sculptor in India and either remained without effect, or was the Indian imitation of a Greek or Achaemenid model, somewhere between the fifth century B.C. and the first century B.C., although it is generally dated from the time of the Maurya Empire, around the 3rd century B.C.[120]

The Pataliputra palace with its pillared hall shows decorative influences of the Achaemenid palaces and Persepolis and may have used the help of foreign craftsmen.[121][1]Mauryan rulers may have even imported craftsmen from abroad to build royal monuments.[122] This may be the result of the formative influence of craftsmen employed from Persia following the disintegration of the Achaemenid Empire after the conquests of Alexander the Great.[123][124] The Pataliputra capital, or also the Hellenistic friezes of the Rampurva capitals, Sankissa, and the diamond throne of Bodh Gaya are other examples.[125]

The renowned Mauryan polish, especially used in the Pillars of Ashoka, may also have been a technique imported from the Achaemenid Empire.[1]

Rock-cut architecture

The similarity of the 4th century BCE Lycian barrel-vaulted tombs, such as the tomb of Payava, in the western part of the Achaemenid Empire, with the Indian architectural design of the Chaitya (starting at least a century later from circa 250 BCE, with the Lomas Rishi caves in the Barabar caves group), suggests that the designs of the Lycian rock-cut tombs travelled to India along the trade routes across the Achaemenid Empire.[127][128]

Early on, James Fergusson, in his " Illustrated Handbook of Architecture", while describing the very progressive evolution from wooden architecture to stone architecture in various ancient civilizations, has commented that "In India, the form and construction of the older Buddhist temples resemble so singularly these examples in Lycia".[129] The structural similarities, down to many architectural details, with the Chaitya-type Indian Buddhist temple designs, such as the "same pointed form of roof, with a ridge", are further developed in The cave temples of India.[130] The Lycian tombs, dated to the 4th century BCE, are either free-standing or rock-cut barrel-vaulted sarcophagi, placed on a high base, with architectural features carved in stone to imitate wooden structures. There are numerous rock-cut equivalents to the free-standing structures and decorated with reliefs.[131][132][133] Fergusson went on to suggest an "Indian connection", and some form of cultural transfer across the Achaemenid Empire.[128] The ancient transfer of Lycian designs for rock-cut monuments to India is considered as "quite probable".[127]

Art historian David Napier has also proposed a reverse relationship, claiming that the Payava tomb was a descendant of an ancient South Asian style, and that Payava may actually have been a Graeco-Indian named "Pallava".[134]

Monumental columns: the Pillars of Ashoka

Regarding the Pillars of Ashoka, there has been much discussion of the extent of influence from Achaemenid Persia,[135] since the column capitals supporting the roofs at Persepolis have similarities, and the "rather cold, hieratic style" of the Sarnath Lion Capital of Ashoka especially shows "obvious Achaemenid and Sargonidinfluence".[136]

Hellenistic influence has also been suggested.[137] In particular the abaci of some of the pillars (especially the Rampurva bull, the Sankissa elephant and the Allahabad pillar capital) use bands of motifs, like the bead and reel pattern, the ovolo, the flame palmettes, lotuses, which likely originated from Greek and Near-Eastern arts.[138]Such examples can also be seen in the remains of the Mauryan capital city of Pataliputra.

Aramaic language and script

The Aramaic language, official language of the Achaemenid Empire, started to be used in the Indian territories.[139] Some of the Edicts of Ashoka in the north-western areas of Ashoka's territory, in modern Pakistan and Afghanistan, used Aramaic (the official language of the former Achaemenid Empire), together with Prakrit and Greek (the language of the neighbouring Greco-Bactriankingdom and the Greek communities in Ashoka's realm).[140]

The Indian Kharosthi script shows a clear dependency on the Aramaic alphabet but with extensive modifications to support the sounds found in Indic languages.[1] One model is that the Aramaic script arrived with the Achaemenid Empire's conquest of the Indus River (modern Pakistan) in 500 BCE and evolved over the next 200+ years, reaching its final form by the 3rd century BCE where it appears in some of the Edicts of Ashoka.[139][1]

Edicts of Ashoka

The Edicts of Ashoka (circa 250 BCE) may show Achaemenid influences, including formulaic parallels with Achaemenid inscriptions, presence of Iranian loanwords (in Aramaic inscriptions), and the very act of engraving edicts on rocks and mountains (compare for example Behistun inscription).[141][142] To describe his own edicts, Ashoka used the word Lipī (????), now generally simply translated as "writing" or "inscription". It is thought the word "lipi", which is also orthographed "dipi" (????) in the two Kharosthi versions of the rock edicts,[b] comes from an Old Persian prototype dipî(????) also meaning "inscription", which is used for example by Darius I in his Behistun inscription,[c] suggesting borrowing and diffusion.[143][144][145] There are other borrowings of Old Persianterms for writing-related words in the Edicts of Ashoka, such as nipista or nipesita ("written" and "made to be written") in the Kharoshthi version of Major Rock Edict No.4, which can be related to the word nipištā ("written") from the daiva inscription of Xerxes at Persepolis.[146]

Several of the Edicts of Ashoka, such as the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription or the Taxila inscription were written in Aramaic, one of the official languages of the former Achaemenid Empire.[147]

Religion

According to Ammianus Marcellinus[149], a 4th century CE Roman author, Hystaspes, the father of Darius I, studied under the Brahmins in India, thus contributing to the development of the religion of the Magi(Zoroastrianism):[150]

In ancient sources, Hystapes is sometimes considered as identical with Vishtaspa (the Avestan and Old Persian name for Hystapes), an early patron of Zoroaster.[150]

Historically, the life of the Buddha also coincided with the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley.[152] The Achaemenid occupation of the areas of Gandara and Hinduš, which was to last for about two centuries, was accompanied by Achaemenid religions, reformed Mazdaism or early Zoroastrianism, to which Buddhism might also have in part reacted.[152] In particular, the ideas of the Buddha may have partly consisted in a rejection of the "absolutist" or "perfectionist" ideas contained in these Achaemenid religions.[152]

Still, according to Christopher I. Beckwith, commenting on the content of the Edicts of Ashoka, the early Buddhist concepts of karma, rebirth, and affirming that good deeds with be rewarded in this life and the next, in Heaven, probably find their origin in Achaemenid Mazdaism, which had been introduced in India from the time of the Achaemenid conquest of Gandara.[153]

See also

Notes

- ^ Ctesias: "The Indians also include this substance among their most precious gifts for the Persian king who receives it as a prize revered above all others."[56]

- ^ For example, according to Hultzsch, the first line of the First Edict at Shahbazgarhi (or at Mansehra) reads: "(Ayam) Dhrama-dipi Devanapriyasa Raño likhapitu" ("This Dharma-Edicts was written by King Devanampriya" Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 51.

This appears in the reading of Hultzsch's original rubbing of the Kharoshthi inscription of the first line of the First Edict at Shahbazgarhi. - ^ For example Column IV, Line 89

'아케메네스 550-330BC' 카테고리의 다른 글

| <펌>Darius the Great : Organizing the Empire - Livius (0) | 2024.06.06 |

|---|---|

| <펌>아케메네스 왕조 (BC 675 - ?, BC 550 - BC330) - 나무위키 (0) | 2019.05.24 |

| <펌>Achaemenid Empire (BC550 - BC 330) (0) | 2019.02.06 |

| <펌> Cyrus the Great (0) | 2019.02.03 |