II. Saka 선조 문명

1. Andronov culture (2000-1150 BC)

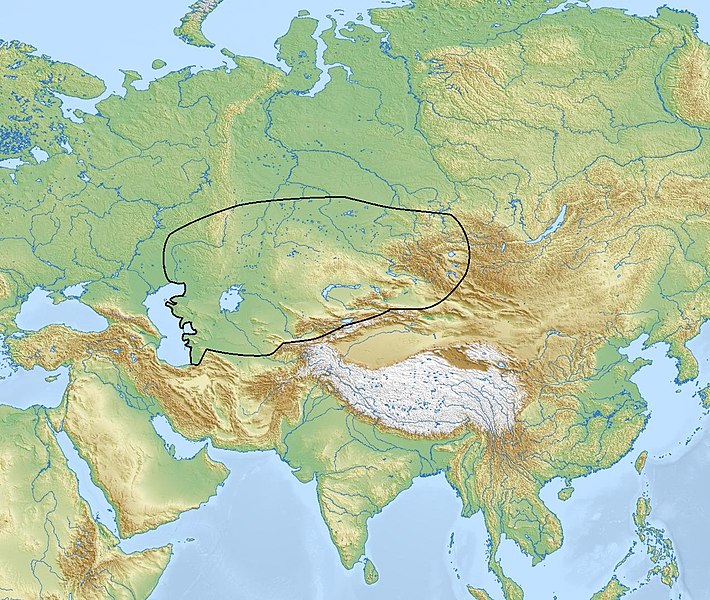

Andronovo culture area

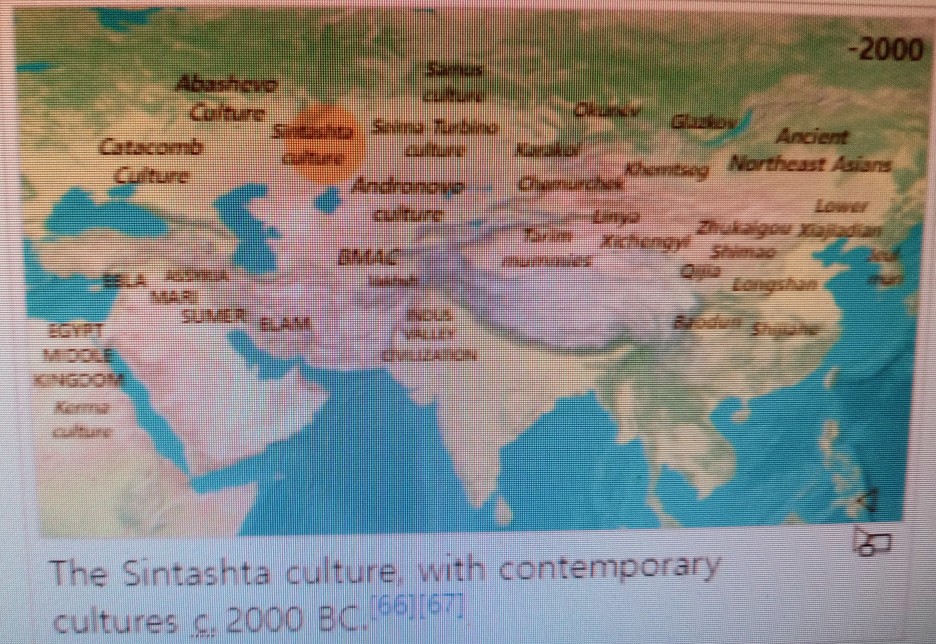

The Andronovo culture[a] is a collection of similar local Late Bronze Age cultures that flourished c. 2000–1150 BC,[1][2][3][4] spanning from the southern Urals to the upper Yenisei River in central Siberia.[5][6] Some researchers have preferred to term it an archaeological complex or archaeological horizon.[7] The slightly older Sintashta culture (c. 2200–1900 BC), formerly included within the Andronovo culture, is now considered separately to Early Andronovo cultures.[8][9] Andronovo culture's first stage could have begun at the end of the 3rd millennium BC, with cattle grazing, as natural fodder was by no means difficult to find in the pastures close to dwellings.[10][11][12]

Most researchers associate the Andronovo horizon with early Indo-Iranian languages, though it may have overlapped the early Uralic-speaking area at its northern fringe.[13] Allentoft et al. (2015) concluded from their genetic studies that the Andronovo culture and the preceding Sintashta culture should be partially derived from the Corded Ware culture, given the higher proportion of ancestry matching the earlier farmers of Europe, similar to the admixture found in the genomes of the Corded Ware population.[14]

Discovery[edit]

The name derives from the village of Andronovo in the Uzhursky District of Kranoyarsk Krai, Siberia, where the Russian zoologist Arkadi Tugarinov discovered its first remains in 1914. Several graves were discovered, with skeletons in crouched positions, buried with richly decorated pottery. The Andronovo culture was first identified by the Russian archaeologist Sergei Teploukhov in the 1920s.[15]

Dating and subcultures[edit]

Archaeological cultures associated with Indo-Iranian migrations (after EIEC): The Andronovo, BMAC and Yaz cultures have often been associated with Indo-Iranian migrations. The Gandhara grave (or Swat), Cemetery H, Copper Hoard and Painted Grey Ware cultures are candidates for the Indo-Aryan migration into South Asia.

The culture of Sarazm (4th–3rd millennium BC) precedes the arrival of the Andronovo steppe culture in South Central Asia in the 2nd millennium BC.[16][17][18]

Currently only two sub-cultures are considered as part of Andronovo culture:[2]

- Alakul (2000–1700 BC)[3] between Oxus (today Amu Darya), and Jaxartes (today Syr Darya), Kyzylkum desert

- Fëdorovo (2000–1450 BC)[19][3] in southern Siberia (earliest evidence of cremation and fire cult[20])

Other authors identified previously the following sub-cultures also as part of Andronovo:

- Eastern Fedorovo (1850–1350 BC)[21][22] in Tian Shan mountains (Northwestern Xinjiang, China), southeastern Kazakhstan, eastern Kyrgyzstan

- Alekseyevka-Sargary (1450–1150 BC)[4][23] "final Bronze Age phase" in eastern Kazakhstan, contacts with Namazga VI in Turkmenia, Ingala Valley in the south of Tyumen Oblast, in Tobol.

Some authors have challenged the chronology and model of eastward spread due to increasing evidence for the earlier presence of these cultural features in parts of east Central Asia.[24]

Geographic extent[edit]

The geographical extent of the culture is vast and difficult to delineate exactly. On its western fringes, it overlaps with the approximately contemporaneous, but distinct, Srubna culture in the Volga-Ural interfluvial. To the east, it reaches into the Minusinsk depression, with some sites as far west as the southern Ural Mountains,[25] overlapping with the area of the earlier Afanasevo culture.[26] Additional sites are scattered as far south as the Koppet Dag (Turkmenistan), the Pamir (Tajikistan) and the Tian Shan (Kyrgyzstan). The northern boundary vaguely corresponds to the beginning of the Taiga.[25] More recently, evidence for the presence of the culture in Xinjiang in far-western China has also been found,[24] mainly concentrated in the area comprising Tashkurgan, Ili, Bortala, and Tacheng area.[27] In the Volga basin, interaction with the Srubna culture was the most intense and prolonged, and Federovo style pottery is found as far west as Volgograd. Mallory notes that the Tazabagyab culture south of Andronovo could be an offshoot of the former (or Srubna), alternatively the result of an amalgamation of steppe cultures and the Central Asian oasis cultures (Bishkent culture and Vakhsh culture).[6]

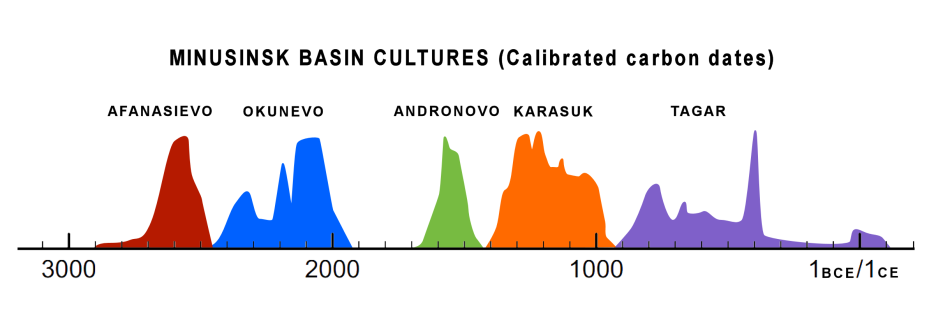

Dates of Minusinsk Basin cultures, at the easternmost edge of Adronovo culture (Summed probability distribution for new human bone dates, Afanasievo to Tagar cultures).[28]

In the initial Sintashta-Petrovka phase,[27] the Andronovo culture is limited to the northern and western steppes in the southern Urals-Kazakhstan.[6] Since then, at the 2nd millennium, in the Alakul Phase (2000–1700 BC),[3] the Fedorovo Phase (1850–1450 BC)[3] and the final Alekseyevka Phase (1400–1000 BC), the Andronovo cultures move intensively eastwards, expanding as far east as the Upper Yenisei River, succeeding the non-Indo-European Okunev culture.[6]

In southern Siberia and Kazakhstan, the Andronovo culture was succeeded by the Karasuk culture (1500–800 BC). On its western border, it is roughly contemporaneous with the Srubna culture, which partly derives from the Abashevo culture. The earliest historical peoples associated with the area are the Cimmerians and Saka/Scythians, appearing in Assyrian records after the decline of the Alekseyevka culture, migrating into Ukraine from ca. the 9th century BC (see also Ukrainian stone stela), and across the Caucasus into Anatolia and Assyria in the late 8th century BC, and possibly also west into Europe as the Thracians (see Thraco-Cimmerian), and the Sigynnae, located by Herodotus beyond the Danube, north of the Thracians, and by Strabo near the Caspian Sea. Both Herodotus and Strabo identify them as Iranian.

2. Sintashta Culture (BC 2200-1900 BC)

Sintashta culture area

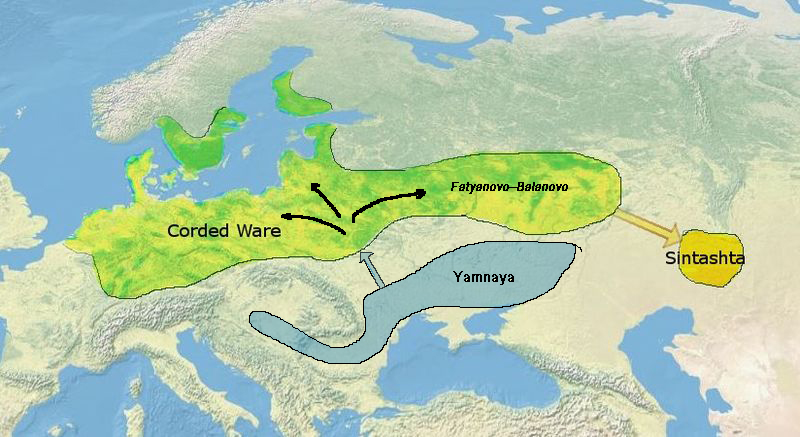

The Sintashta culture[a] is a Middle Bronze Age archaeological culture of the Southern Urals,[1] dated to the period c. 2200–1900 BCE.[2][3] It is the first phase of the Sintashta–Petrovka complex,[4] c. 2200–1750 BCE. The culture is named after the Sintashta archaeological site, in Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, and spreads through Orenburg Oblast, Bashkortostan, and Northern Kazakhstan. The Sintashta culture is thought to represent an eastward migration of peoples from the Corded Ware culture.[5][6][7][8] It is widely regarded as the origin of the Indo-Iranian languages (Indo-Iranic languages[9][10]),[11][12][13] whose speakers originally referred to themselves as the Arya.[14][15]

The earliest known chariots have been found in Sintashta burials, and the culture is considered a strong candidate for the origin of the technology, which spread throughout the Old World and played an important role in ancient warfare.[16][17][18][19] Sintashta settlements are also remarkable for the intensity of copper mining and bronze metallurgy carried out there, which is unusual for a steppe culture.[20] Among the main features of the Sintashta culture are high levels of militarism and extensive fortified settlements, of which 23 are known.[21]

Origin[edit]

According to Allentoft et al. (2015), the Sintashta culture probably derived at least partially from the Corded Ware culture

Because of the difficulty of identifying the remains of Sintashta sites beneath those of later settlements, the culture was only distinguished in the 1990s from the Andronovo culture.[22] It was then recognised as a distinct entity, forming part of the "Andronovo horizon". Koryakova (1998) concluded from their archaeological findings that the Sintashta culture originated from the interaction of the two precursors Poltavka culture and Abashevo culture. Allentoft et al. (2015) concluded from their genetic results that the Sintashta culture should have emerged from an eastward migration of peoples from the Corded Ware culture.[23] In addition, Narasimshan et al. (2019) cautiously cite that "morphological data has been interpreted as suggesting that both Fedorovka and Alakul’ skeletons are similar to Sintashta groups, which in turn may reflect admixture of Neolithic forest HGs and steppe pastoralists, descendants of the Catacomb and Poltavka cultures".[24]

Sintashta emerged during a period of climatic change that saw the already arid Kazakh steppe region become even colder and drier. The marshy lowlands around the Ural and upper Tobol rivers, previously favoured as winter refuges, became increasingly important for survival.[citation needed] Under these pressures both Poltavka and Abashevo herders settled permanently in river valley strongholds, eschewing more defensible hill-top locations.[25]

Its immediate predecessor in the Ural-Tobol steppe was the Poltavka culture, an offshoot of the cattle-herding Yamnaya horizon that moved east into the region between 2800 and 2600 BCE. Several Sintashta towns were built over older Poltavka settlements or close to Poltavka cemeteries, and Poltavka motifs are common on Sintashta pottery.[26]

Sintashta material culture also shows the influence of the late Abashevo culture, derived from the Fatyanovo-Balanovo culture, a collection of Corded Ware settlements in the forest steppe zone north of the Sintashta region that were also predominantly pastoralist.....

Linguistic identity[edit]

Main articles: Proto-Indo-Iranic and Indo-Iranic peoples

See also: Indo-Iranic languages

Chariot model, Arkaim museum

Anthony (2007) assumes that probably the people of the Sintashta culture spoke "Common-Indo-Iranian". This identification is based primarily on similarities between sections of the Rig Veda, a religious text which includes ancient Indo-Iranian hymns recorded in Vedic Sanskrit, and the funerary rituals of the Sintashta culture as revealed by archaeology.[12] Some cultural similarities with Sintashta have also been found to be common with the Nordic Bronze Age of Scandinavia.[40]

There is linguistic evidence of interaction between Finno-Ugric and Indo-Iranian languages, showing influences from the Indo-Iranians into the Finno-Ugric culture.[41][42]

From the Sintashta culture the Indo-Iranian followed the migrations of the Indo-Iranians to Anatolia, the Iranian plateau and the Indian subcontintinent.[43][44] From the 9th century BCE onward, Iranian languages also migrated westward with the Scythians back to the Pontic steppe where the proto-Indo-Europeans came from.[44]

Warfare[edit]

Horses were domesticated on the Pontic-Caspian steppe[45]

The preceding Abashevo culture was already marked by endemic intertribal warfare;[46] intensified by ecological stress and competition for resources in the Sintashta period. This drove the construction of fortifications on an unprecedented scale and innovations in military technique such as the invention of the war chariot. Increased competition between tribal groups may also explain the extravagant sacrifices seen in Sintashta burials, as rivals sought to outdo one another in acts of conspicuous consumption analogous to the North American potlatch tradition.[25]

Sintashta artefact types such as spearheads, trilobed arrowheads, chisels, and large shaft-hole axes were taken east.[47] Many Sintashta graves are furnished with weapons, although the composite bow associated later with chariotry does not appear. Higher-status grave goods include chariots, as well as axes, mace-heads, spearheads, and cheek-pieces. Sintashta sites have produced finds of horn and bone, interpreted as furniture (grips, arrow rests, bow ends, string loops) of bows; there is no indication that the bending parts of these bows included anything other than wood.[48]

Arrowheads are also found, made of stone or bone rather than metal. These arrows are short, 50–70 cm long, and the bows themselves may have been correspondingly short.[48]

Sintashta culture, and the chariot, are also strongly associated with the ancestors of modern domestic horses, the DOM2 population. DOM2 horses originated from the Western Eurasia steppes, especially the lower Volga-Don, but not in Anatolia, during the late fourth and early third millennia BCE. Their genes may show selection for easier domestication and stronger backs.[49]

Metal production[edit]

|

External videos

|

|

|

The Sintashta culture - earliest chariots, fortified settlements and bronze metallurgy. Ivan Semyan

|

The Sintashta economy came to revolve around copper metallurgy. Copper ores from nearby mines (such as Vorovskaya Yama) were taken to Sintashta settlements to be processed into copper and arsenical bronze. This occurred on an industrial scale: all the excavated buildings at the Sintashta sites of Sintashta, Arkaim and Ust'e contained the remains of smelting ovens and slag.[25] Around 10% of graves, mostly adult male, contained artifacts related to bronze metallurgy (molds, ceramic nozzles, ore and slag remains, metal bars and drops). However, these metal-production related grave goods rarely co-occur with higher-status grave goods. This likely means that those who engaged in metal production were not at the top of the social-hierarchy, even though being buried at a cemetery evidences some sort of higher status.[50]

Much of Sintashta metal was destined for export to the cities of the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) in Central Asia. The metal trade between Sintashta and the BMAC for the first time connected the steppe region to the ancient urban civilisations of the Near East: the empires and city-states of modern Iran and Mesopotamia provided a large market for metals. These trade routes later became the vehicle through which horses, chariots and ultimately Indo-Iranian-speaking people entered the Near East from the steppe.[51][52]

(source : Sintashta culture, wikipedia, 인용출처 : 본 블로그,)

3. Srubnaya culture (BC 1900-BC 1200)

|

|

|

Geographical range

|

Pontic steppe

|

|

Period

|

Bronze Age

|

|

Dates

|

ca. 1900 BC – 1200 BC

|

|

Preceded by

|

Abashevo culture, Multi-cordoned ware culture, Sintashta culture, Lola culture

|

|

Followed by

|

Noua-Sabatinovka culture, Trzciniec culture, Belozerka culture, Bondarikha culture, Sauromatians

|

The Srubnaya culture (Russian: Срубная культура, romanized: Srubnaya kul'tura, Ukrainian: Зрубна культура, romanized: Zrubna kul'tura), also known as Timber-grave culture, was a Late Bronze Age 1900–1200 BC culture[1][2][3] in the eastern part of the Pontic–Caspian steppe. It is a successor of the Yamna culture, the Catacomb culture and the Poltavka culture. It is co-ordinate and probably closely related to the Andronovo culture, its eastern neighbor.[3] Whether the Srubnaya culture originated in the east, west, or was a local development, is disputed among archaeologists.[3]

The Srubnaya culture is generally associated with archaic Iranian-speakers.[3][4] The name comes from Russian сруб (srub), "timber framework", from the way graves were constructed.

Distribution[edit]

Chariot model, Arkaim museum

Srubnaya blades

The Srubnaya culture occupied the area along and above the north shore of the Black Sea from the Dnieper eastwards along the northern base of the Caucasus to the area abutting the north shore of the Caspian Sea, west of the Ural Mountains.[3] Historical testimony indicate that the Srubnaya culture was succeeded by the Scythians.[3]

Characteristics[edit]

The Srubnaya culture is named for its use of timber constructions within its burial pits. Its cemeteries consisted of five to ten kurgans. Burials included the skulls and forelegs of animals and ritual hearths. Stone cists were occasionally employed.[3] Srubnaya settlements consisted of semi-subterranean and two-roomed houses. The presence of bronze sickles, grinding stones, domestic cattle, sheep and pigs indicate that the Srubnaya engaged in both agriculture and stockbreeding.[3]

The use of chariots in the Srubnaya culture is indicated by finds of studded antler cheek-pieces (for controlling chariot horses), burials of paired domesticated horses, and ceramic vessels with images of two-wheeled vehicles on them.[5][6] The predecessor of the Srubnaya culture, a variant of the Abashevo culture known as the Pokrovka type, is considered to be an important part of the early ‘chariot horizon’, representing the rapid spread of the 'chariot complex'.[7][8]

Language[edit]

The Srubnaya culture is generally considered to have been Iranian.[3][4] Its area, which coincides with the presence of Iranian hydronyms,[4] has been suggested as a staging region from which the Iranian peoples migrated across the Caucasus into the Iranian Plateau.[3]

Genetics[edit]

See also: Fatyanovo-Balanovo culture § Genetics, Sintashta culture § Genetics, and Andronovo culture § Genetics

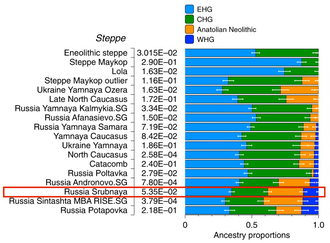

Admixture proportions of Srubnaya populations. They combined Eastern Hunter Gatherer ( EHG), Caucasian Hunter-Gatherer ( CHG), Anatolian Neolithic ( ) and Western Hunter Gatherer ( WHG) ancestry.[9]

Mathieson et al. (2015)[10] surveyed 14 individuals of the Srubnaya culture. Six men from 5 different cemeteries belonged to the Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a1. Extractions of mtDNA from fourteen individuals were determined to represent five samples of haplogroup H, four samples of haplogroup U5, two samples of T1, one sample of T2, one sample of K1b, one of J2b and one of I1a.

A 2017 genetic study published in Scientific Reports found that the Scythians shared similar mitochondrial lineages with the Srubnaya culture. The authors of the study suggested that the Srubnaya culture was ancestral to the Scythians.[11]

In 2018, a genetic study of the earlier Srubnaya culture, and later peoples of the Scythian cultures, including the Cimmerians, Scythians, Sarmatians, was published in Science Advances. Six males from two sites ascribed to the Srubnaya culture were analysed, and were all found to possess haplogroup R1a1a1. Cimmerian, Sarmatian and Scythian males were however found have mostly haplogroup R1b1a1a2, although one Sarmatian male carried haplogroup R1a1a1. The authors of the study suggested that rather than being ancestral to the Scythians, the Srubnaya shared with them a common origin from the earlier Yamnaya culture.[12]

In a genetic study published in Science in 2018, the remains of twelve individuals ascribed to the Srubnaya culture was analyzed. Of the six samples of Y-DNA extracted, three belonged to R1a1a1b2 or subclades of it, one belonged to R1, one belonged to R1a1, and one belonged to R1a1a. With regards to mtDNA, five samples belonged to subclades of U, five belonged to subclades of H, and two belonged to subclades of T. People of the Srubnaya culture were found to be closely related to people of the Corded Ware culture, the Sintashta culture, Potapovka culture and the Andronovo culture.[a][b] These were found to harbor mixed ancestry from the Yamnaya culture and peoples of the Central European Middle Neolithic.[13] The genetic data suggested that these cultures were ultimately derived of a remigration of Central European peoples with steppe ancestry back into the steppe.[c]

In a 2023 study, one sample from the site Nepluyevsky, belonging to Srubnaya-Alakul culture and located in Southern Urals, (c. 1877 to 1642 calBC), (2-sigma, 95.4%), featured Y-haplogroup R1a1a1b2a (R1a-Z94), and other not dated sample featured R1a1a1b2 (R1a-Z93).[14]

Gallery[edit]

- Ceramic sherd

- Bronze axes

- Horse bridle items

- Reconstructed Srubnaya hut

- Timber grave and tumulus

- Dispersion of double-horse burials ca. 2000-1400/1300 BCE.[15] Horses were domesticated on the Pontic-Caspian steppe.[16]

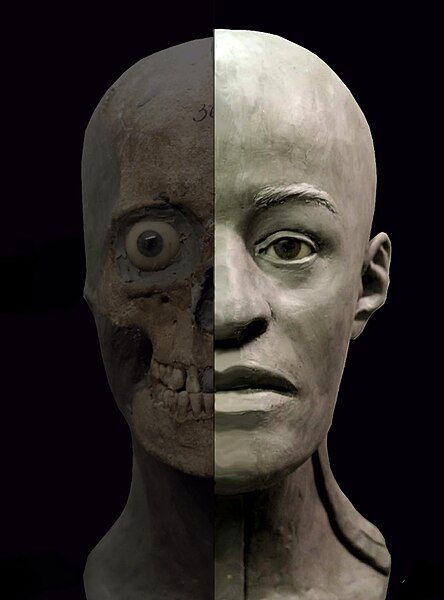

- Forensic reconstruction of a young woman (20-25), from the Aksay I cemetery, kurgan 9, burial 6, Late Bronze Age, Srubnaya culture.[17]

'Scythians Saka' 카테고리의 다른 글

| <펌>Targitaos (0) | 2024.05.25 |

|---|---|

| 스키타인에 대한 자료(3):스키타인 문화 (0) | 2024.05.10 |

| <펌>Scythians - wikipedia (0) | 2024.04.10 |

| Saka인에 대한 자료 (0) | 2024.02.20 |

| 스키타인에 대한 자료 (0) | 2024.02.20 |